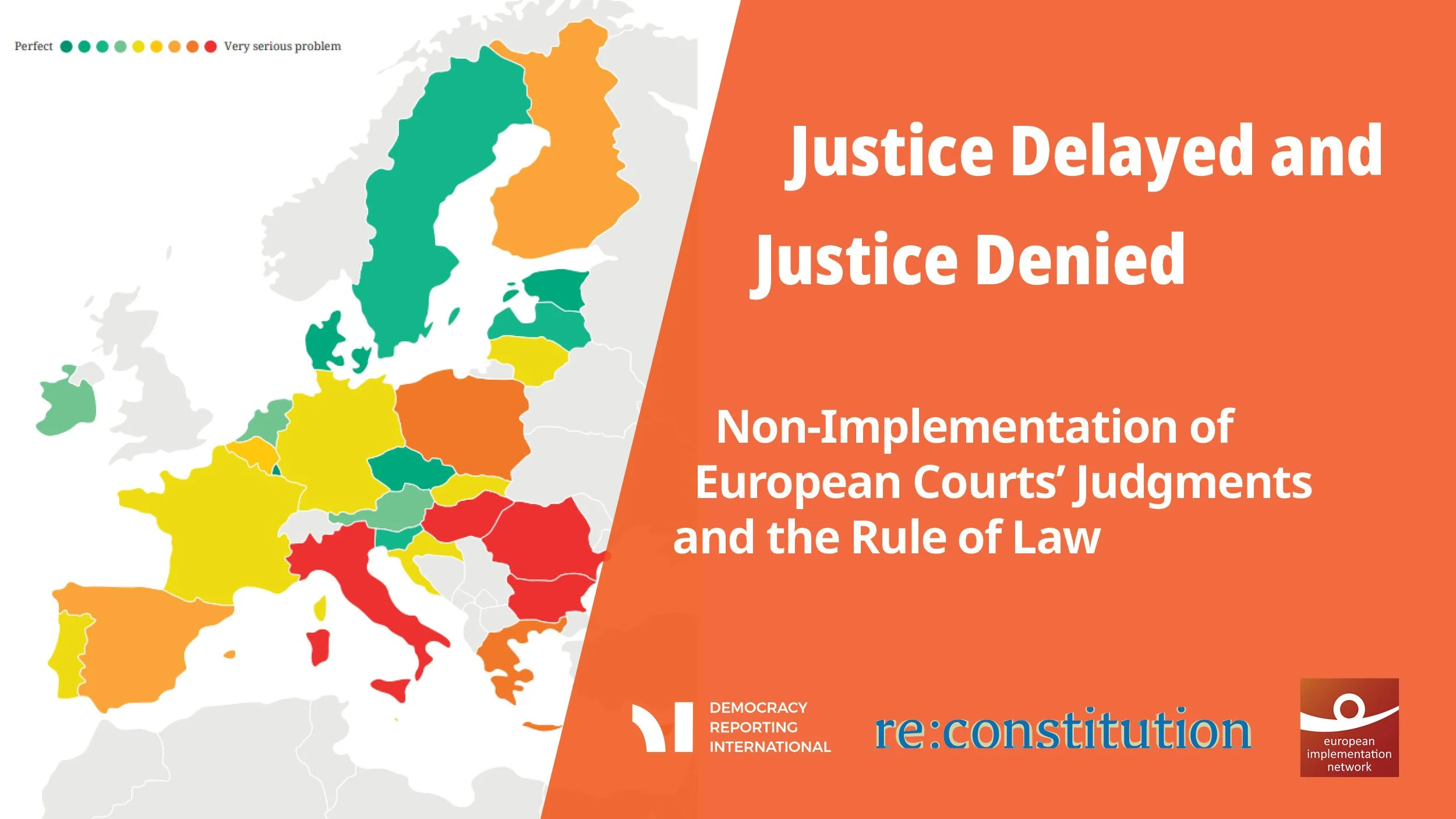

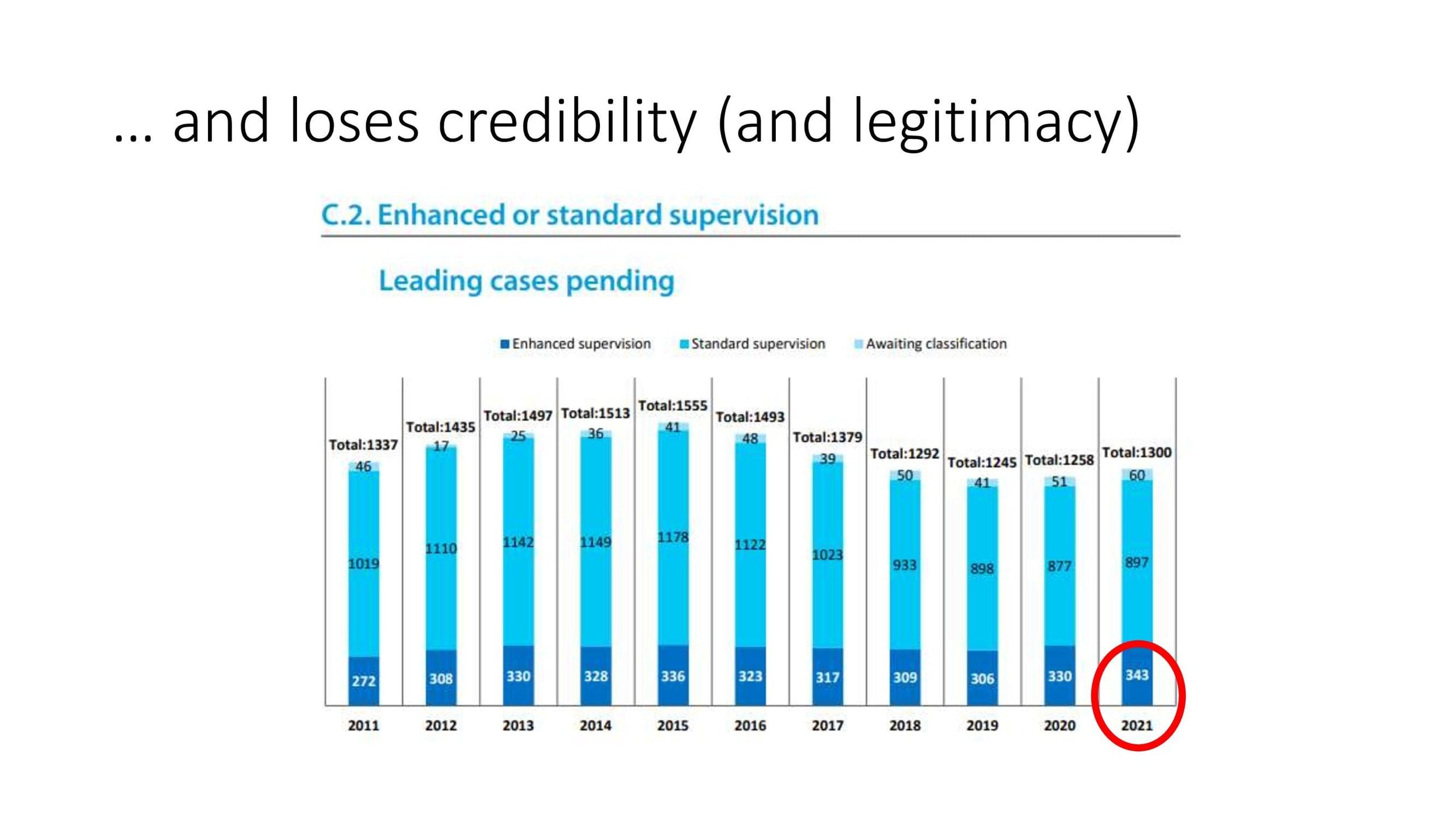

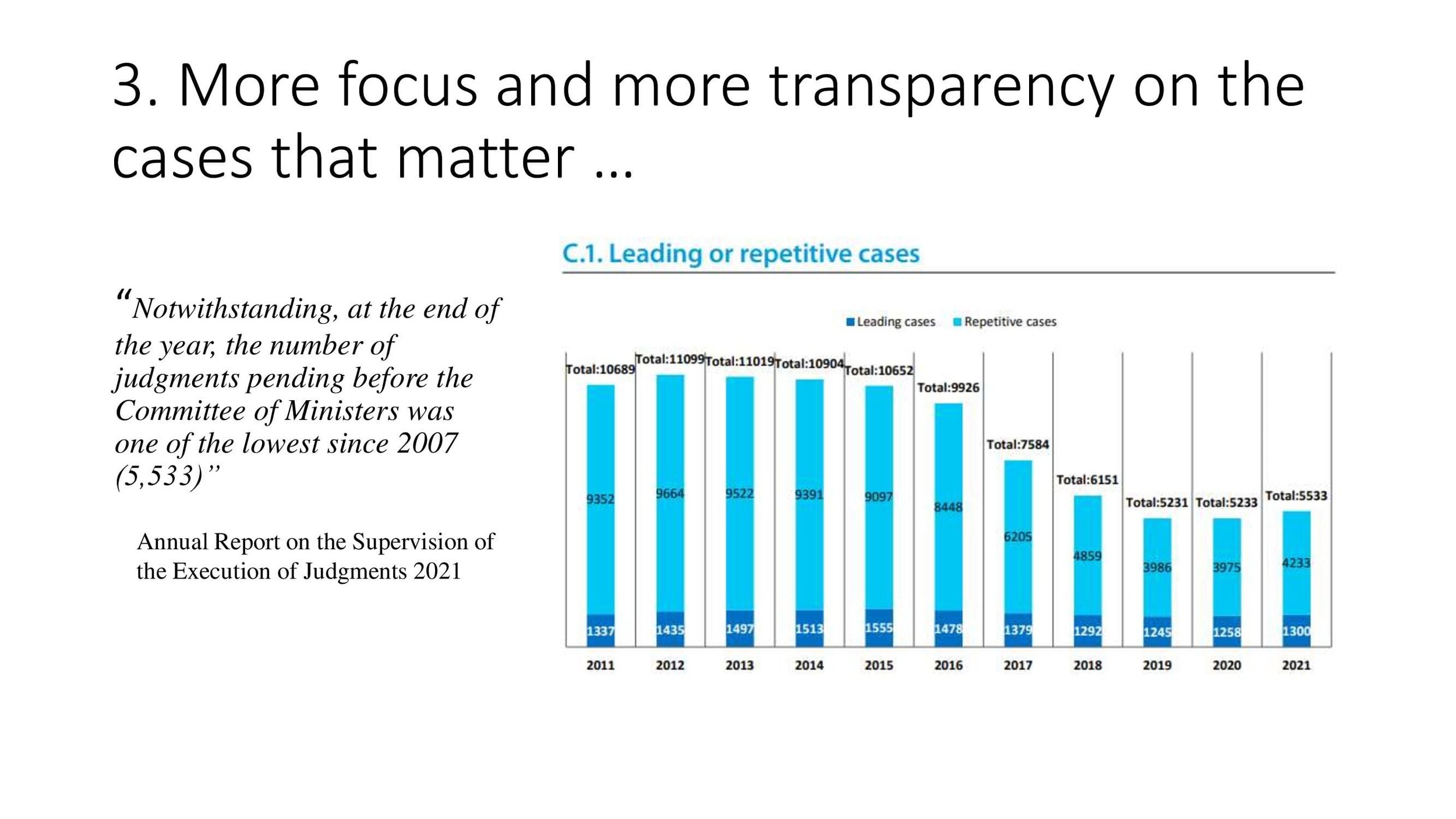

As of 1 January 2022, there are 1300 leading judgments pending implementation. Each of these represents a distinct structural and/or systemic human rights problem. This number has been rising, meaning that the problem with non-implementation is getting worse.

Moreover, the average time that the 1300 leading judgments have been pending implementation is over six years. Furthermore, 47% of the leading ECtHR judgments from the last ten years are still pending implementation.

The data indicates that there is a systemic problem with the implementation of leading judgments of the ECtHR and that the situation is becoming more serious every year.

2. The non-implementation problem has very serious negative effects for the protection of democracy, human rights and the rule of law – threatening the existence of the ECHR system itself.

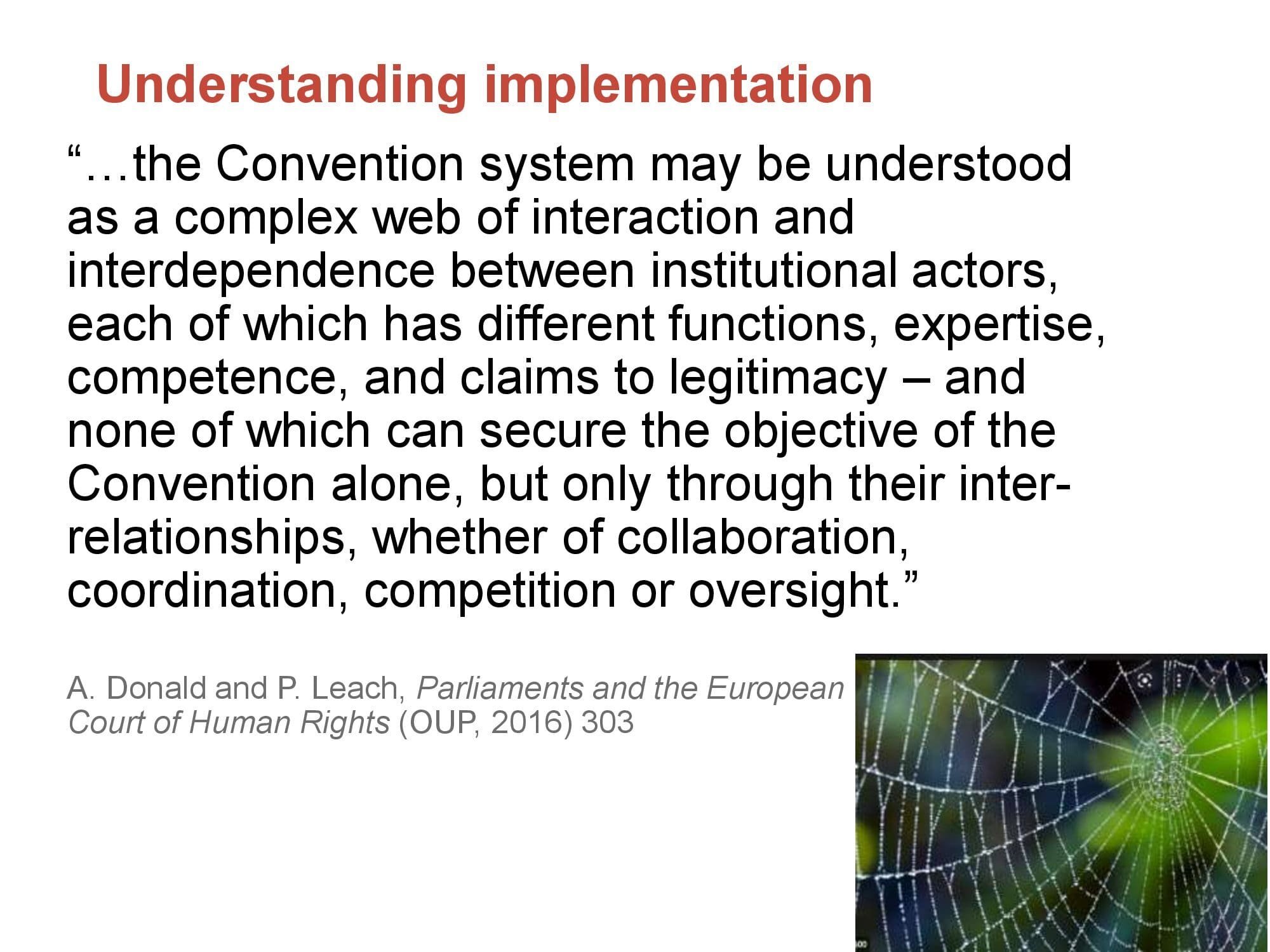

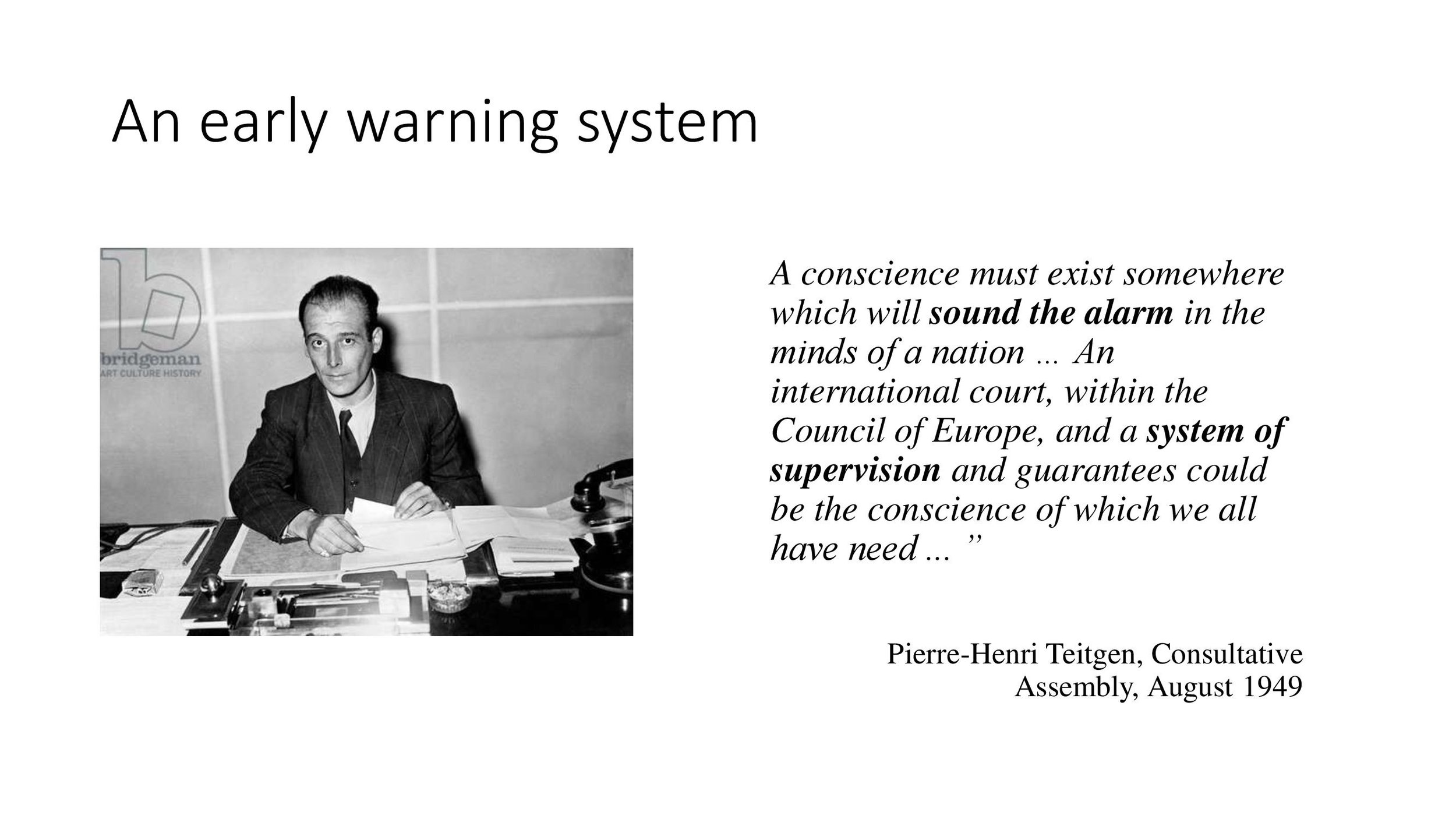

The European Convention on Human Rights was created in the aftermath of World War II, as an early-warning system to identify and halt, amongst other things, the re-emergence of totalitarianism. Under the Convention system, the ECtHR would provide an objective analysis of whether a country’s laws and policies violated fundamental values, under the Court’s interpretation of the ECHR. The collective monitoring of the execution of judgments by the Committee of Ministers was further envisaged to bring peer pressure on countries that have been found to violate the Convention.

The ECHR system is designed not only to identify violations of human rights, but also to remedy them. The non-implementation of leading ECtHR judgments means that this system is not working effectively.

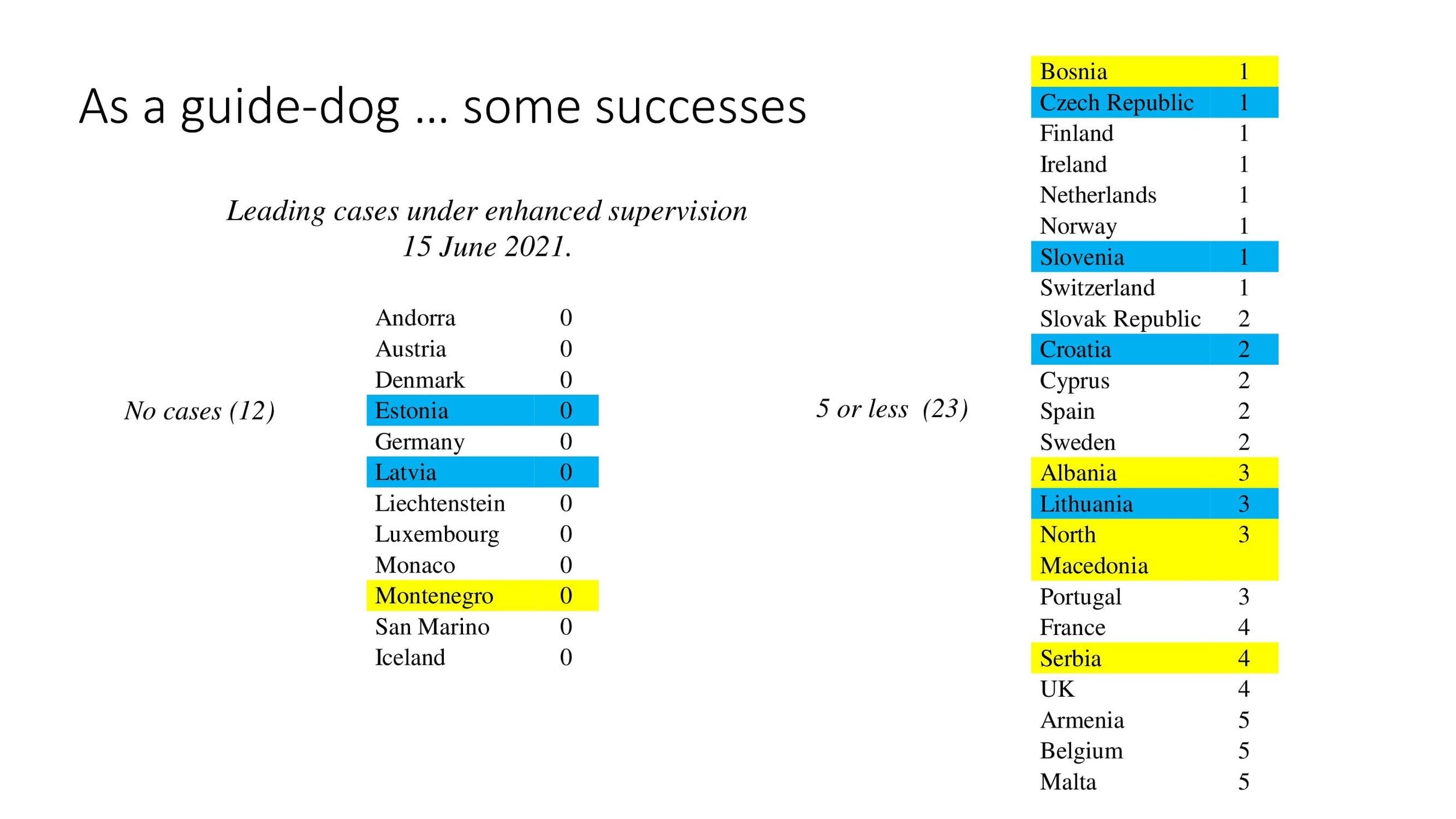

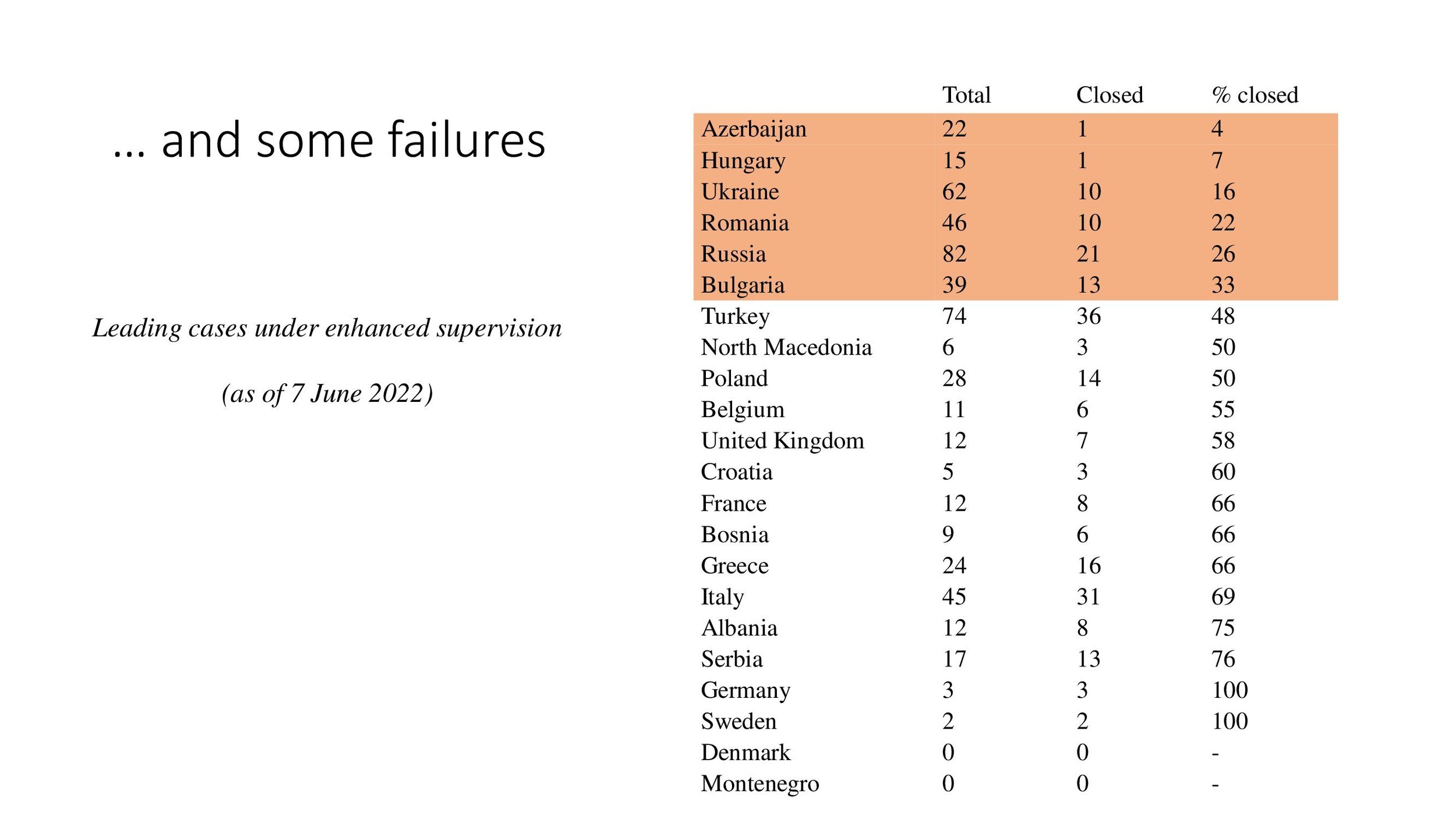

It is important to note that this issue is not confined to a particular country, or a particular part of the continent. The non-implementation of ECtHR judgments is a problem that is manifest across the entire Council of Europe. According to the Council’s latest annual report on the execution of ECtHR judgments, a total of 27 states have 10 or more leading judgments pending implementation: Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Malta, North Macedonia, Poland, Portugal, Romania, the Russian Federation, Serbia, the Slovak Republic, Spain, Turkey, Ukraine and the United Kingdom.

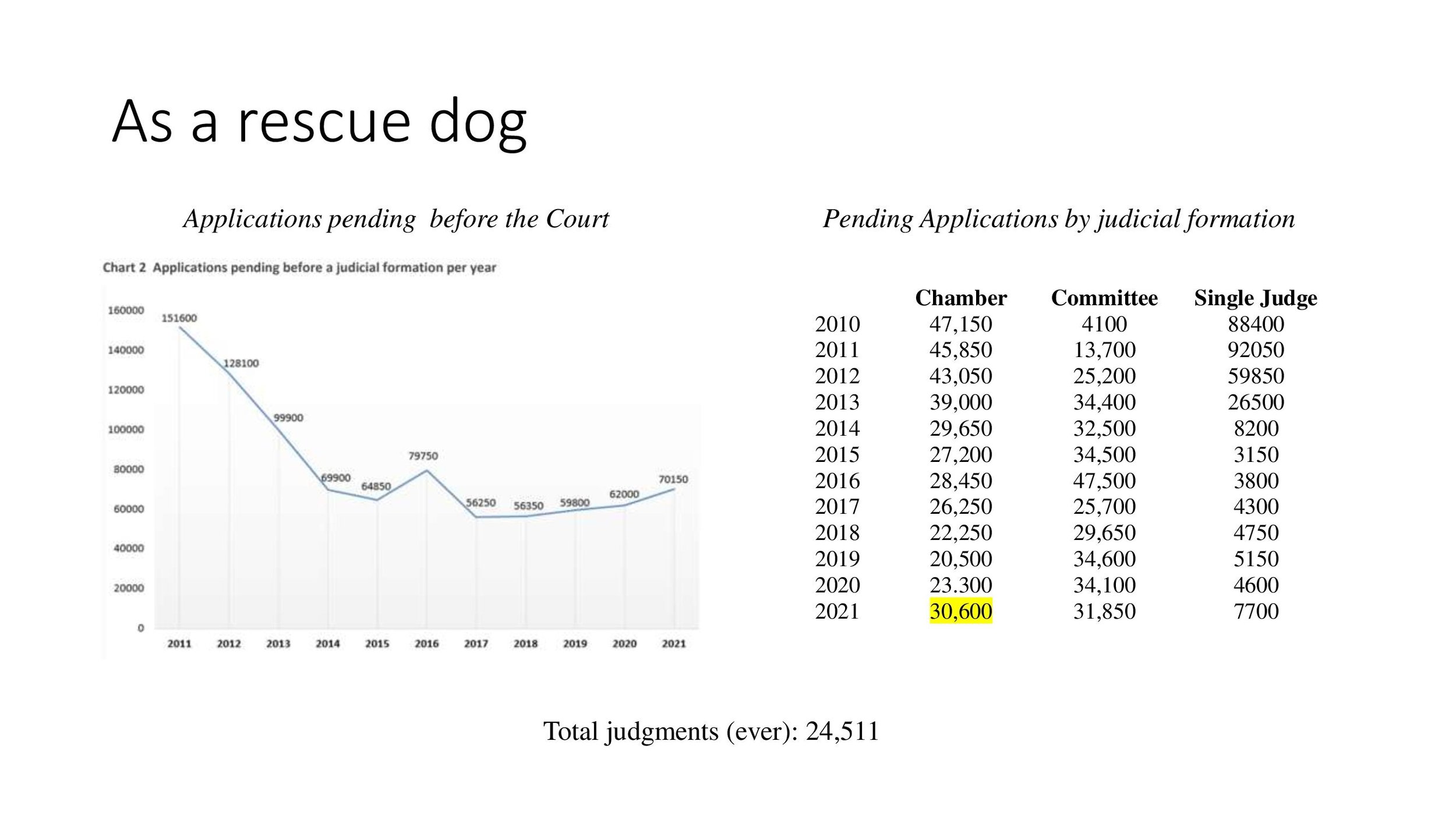

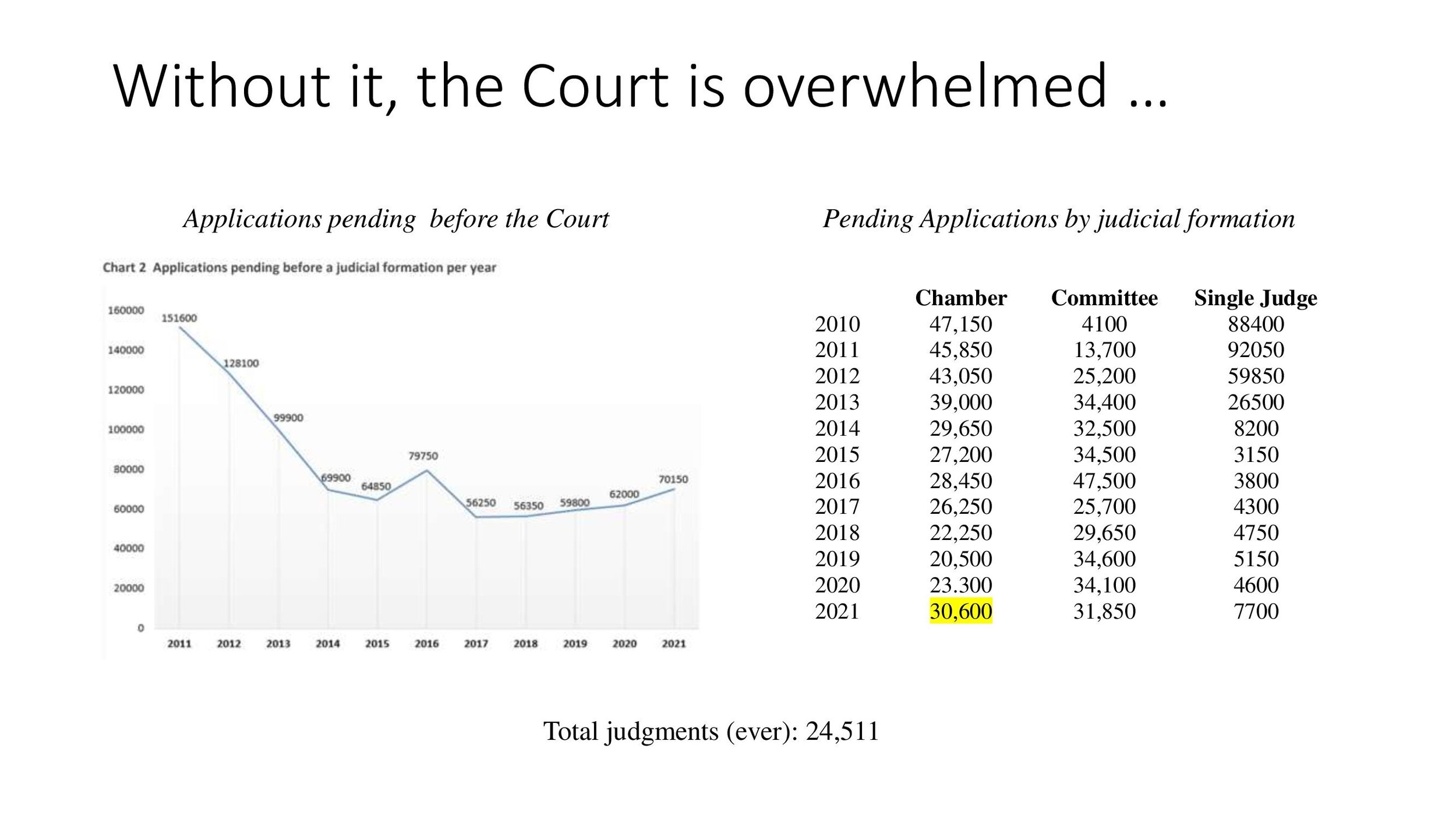

In total, there are 1300 human rights problems identified by the ECtHR in leading judgments which have not been resolved. The most important aspect of the non-implementation of the 1300 pending leading judgments is that they threaten not only the protection of human rights, democracy, and the rule of law, but the existence of the ECtHR itself. Failing to resolve the human rights problems identified in leading judgments means that the same violations keep happening, and more applications come to the Strasbourg Court. There are now around 70,000 applications pending examination before a judicial formation at the ECtHR. The re-occurrence of violations and the resulting avalanche of applications is directly linked to the non-implementation of judgments.

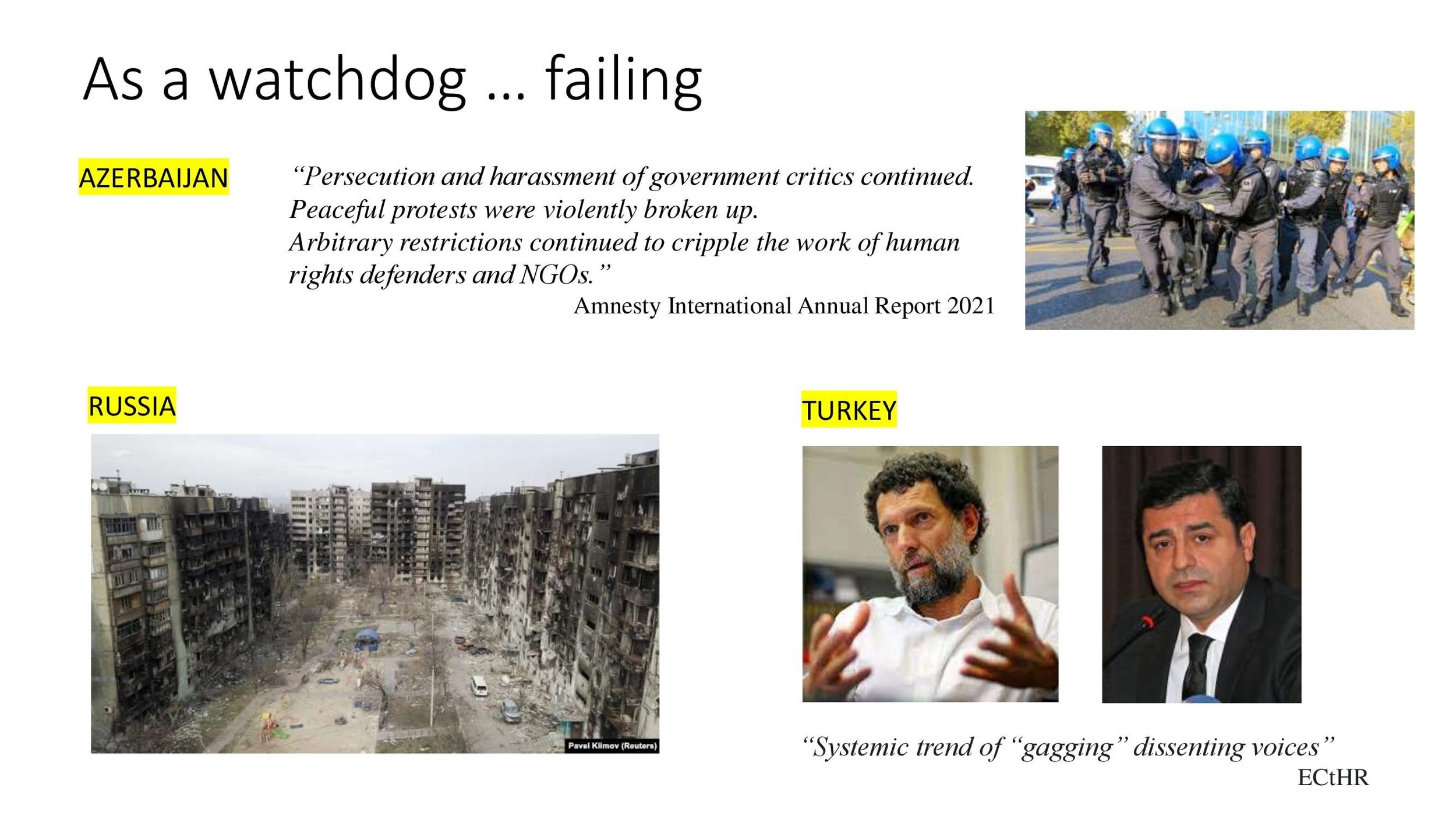

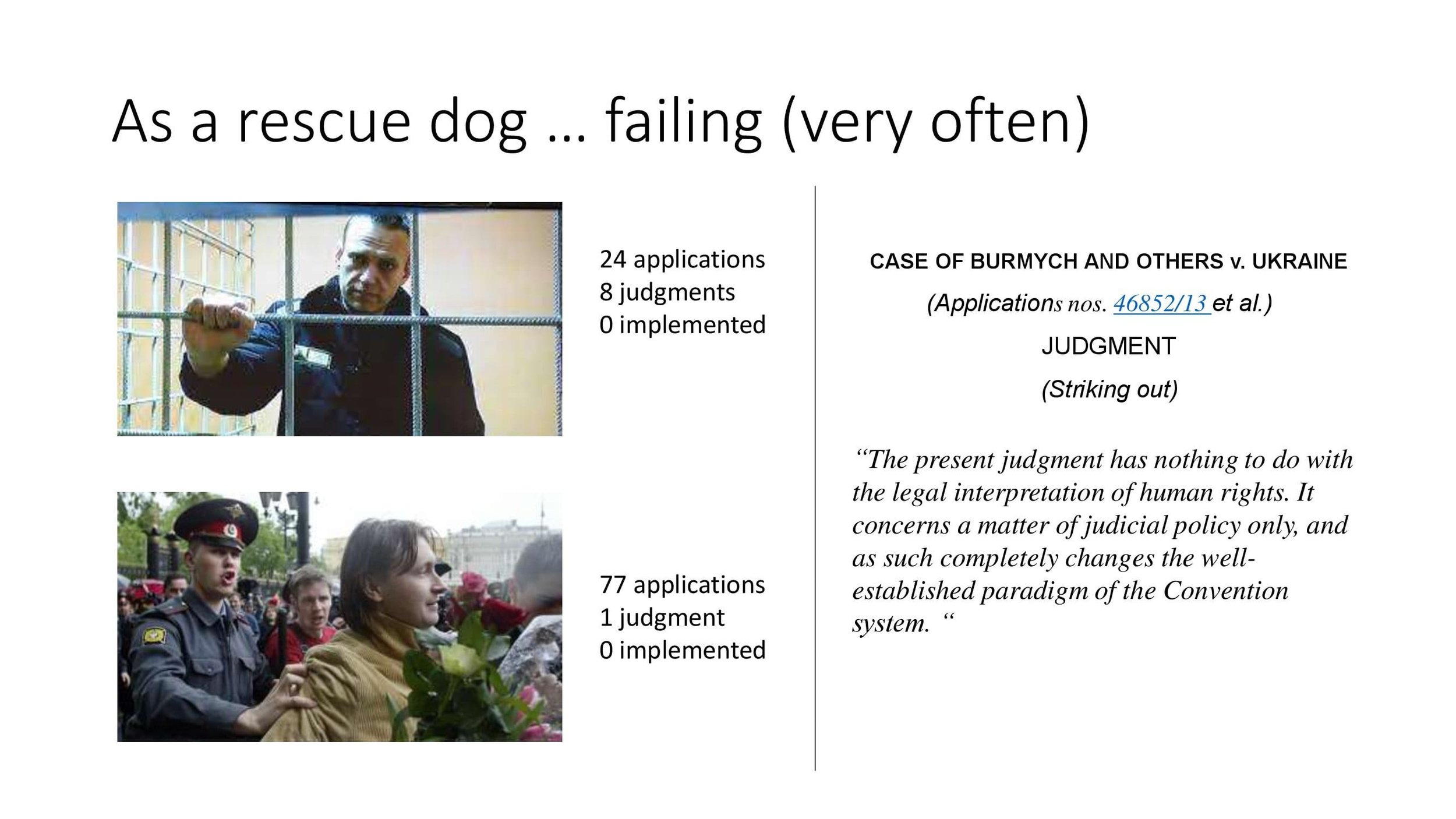

One of the many examples of this urgent problem has been the non-implementation of judgments by Russian Federation. Russia has the highest number of unimplemented leading ECtHR judgments out of any state. 214 leading judgments against Russia have never been implemented. This includes 90% of the leading judgments against Russia from the last ten years. Leading judgments from the ECtHR have highlighted the unlawful jailing of opposition figures, systematic bans on freedom of assembly, censorship, and limitless government surveillance. However, the Russian authorities have not remedied these systemic issues. These measures have been relied upon by the Russian authorities to prevent and quash public opposition to the invasion of Ukraine.

3. The Council of Europe is failing to carry out a strategy capable of addressing the issue, apparently due to budgetary constraints.

At the meeting of the Committee of Ministers in Hamburg in May 2021, the Committee endorsed the strategic framework for the Council of Europe put forward by the Secretary General, for the period 2021-2024. The number one priority in the strategic framework is the implementation of the ECHR at national level and the implementation of ECtHR judgments.

However, one year after ECtHR implementation became a top strategic priority, it is not clear that this has also resulted in the identification of means which are capable of addressing the problem (such as those we set out below in section 4).

The part of the Council of Europe which is chiefly responsible for the implementation of ECtHR judgments is the Department for the Execution of Judgments. According to the Programme and Budget for 2022-2025, the department’s budget will stay the same in real terms as compared to 2021. The fact that there is a lack of much-needed additional resourcing for the Department is recognised in the Council of Europe’s 2021 Annual Report on the Supervision of the Execution of Judgments of the ECtHR. In the report, the Director General of the Directorate General of Human Rights and Rule of Law, Christos Giakoumopoulos, notes that the Department for the Execution of Judgments is vital to the implementation process, and that, “For this reason, its resources, which are already extremely strained, need to be urgently strengthened” (page 32). These resources have not been strengthened and we have seen no plan to do this.

In terms of technical co-operation projects, the 2022-2025 budget identifies only one project to address the non-implementation of leading judgments (“Reducing the backlog of outstanding unexecuted leading judgments of the European Court of Human Rights”). This project has not received any funding from the ordinary budget and will rely on voluntary contributions (which may or may not arrive). Even if it is resourced, it will have a maximum budget of 1.3 million euros per year. This budget is too small to promote the implementation of 1300 leading judgments in 47 states. A Council of Europe project aiming to promote the implementation of just a few judgments in one state normally runs to hundreds of thousands of euros per year (see this example).

In terms of the work in standard-setting, the CDDH working group DH-SYSC V is currently preparing guidelines for states “to prevent and remedy violations of the European Convention on Human Rights” – including guidance on effectively implementing judgments of the ECtHR. They are due to be delivered before the end of 2023. These new guidelines are welcome; however, they will not be capable of addressing the implementation problem on their own. There have already been recommendations from the Committee of Ministers on this subject, which have not proved capable of preventing the implementation problem from worsening. For example, “Recommendation CM/Rec(2008)2 on efficient domestic capacity for rapid execution of judgments of the European Court of Human Rights” is named by DH-SYSCH V as one of 13 different recommendations and guidelines previously published by the Council of Europe concerning the prevention of violations of the Convention at the national level and the improvement of domestic remedies (see page 10 of the recent meeting report). Without more activities from the Council of Europe, including increased resources for the Department for the Execution of Judgments and dedicated co-operation projects, the new guidelines will remain theoretical and will not be put into practice where they are needed most.

Overall, there is an absence of a well-resourced implementation strategy that the ECHR system desperately needs.

4. The Council of Europe should formulate an effective public strategy to address the systemic non-implementation of ECtHR judgments – and ensure it is properly resourced.

If it has not already done so, the Council of Europe must formulate a strategy that is capable of addressing the systemic non-implementation of ECtHR judgments; publish this strategy; and ensure that it is adequately resourced.

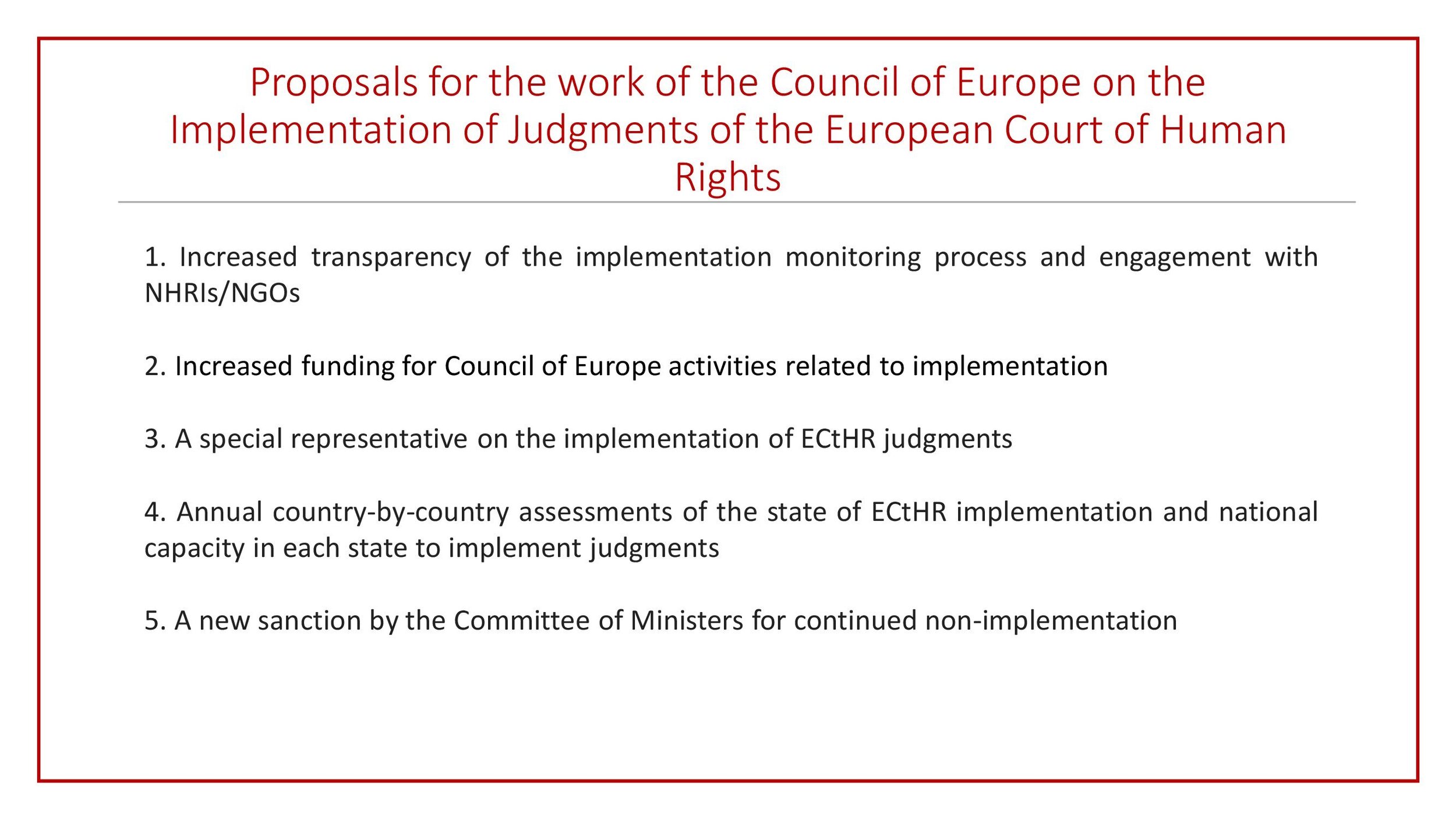

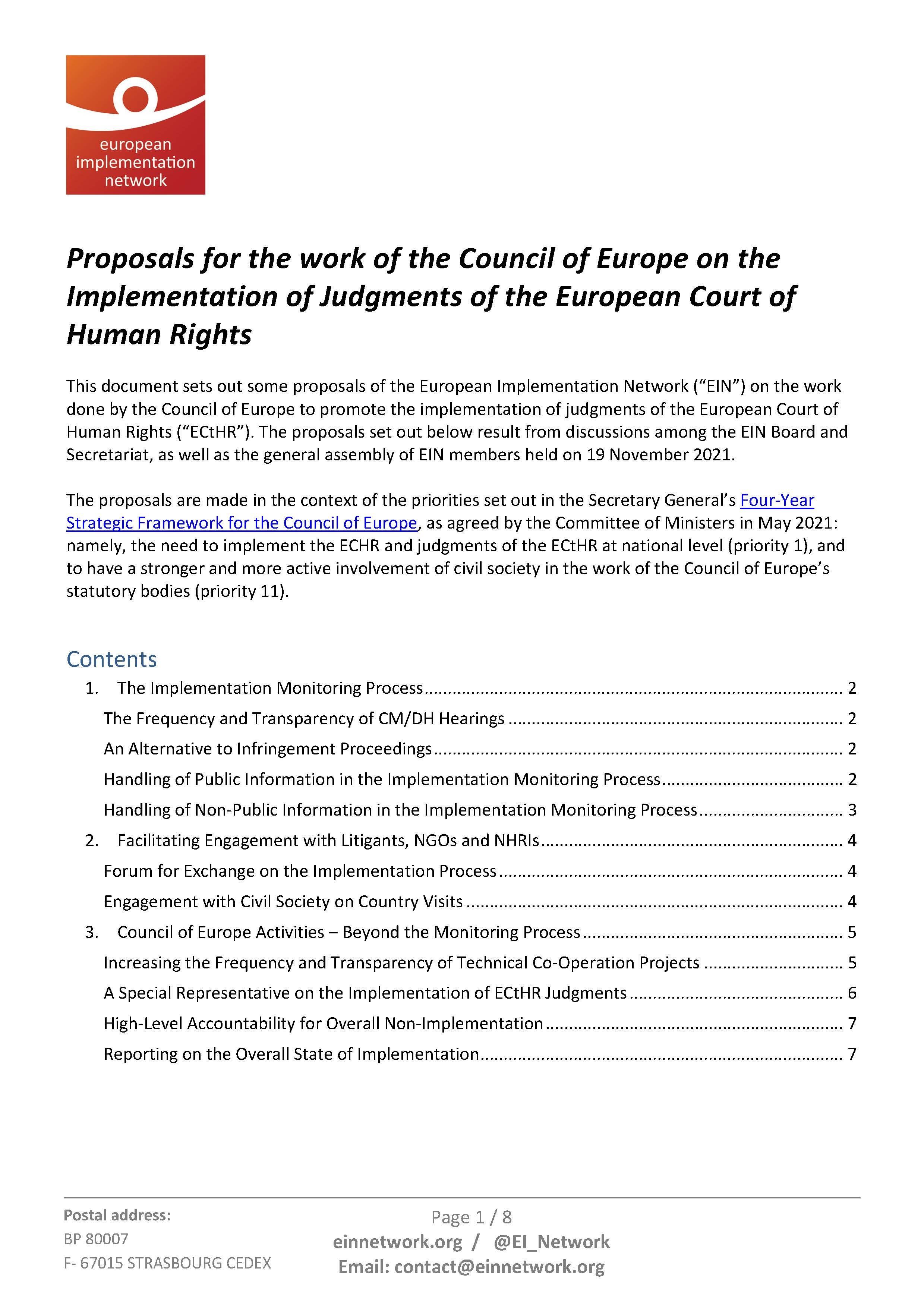

EIN has drafted a series of recommendations that would promote the implementation of ECtHR judgments, which are provided in the attached document. Key proposals include:

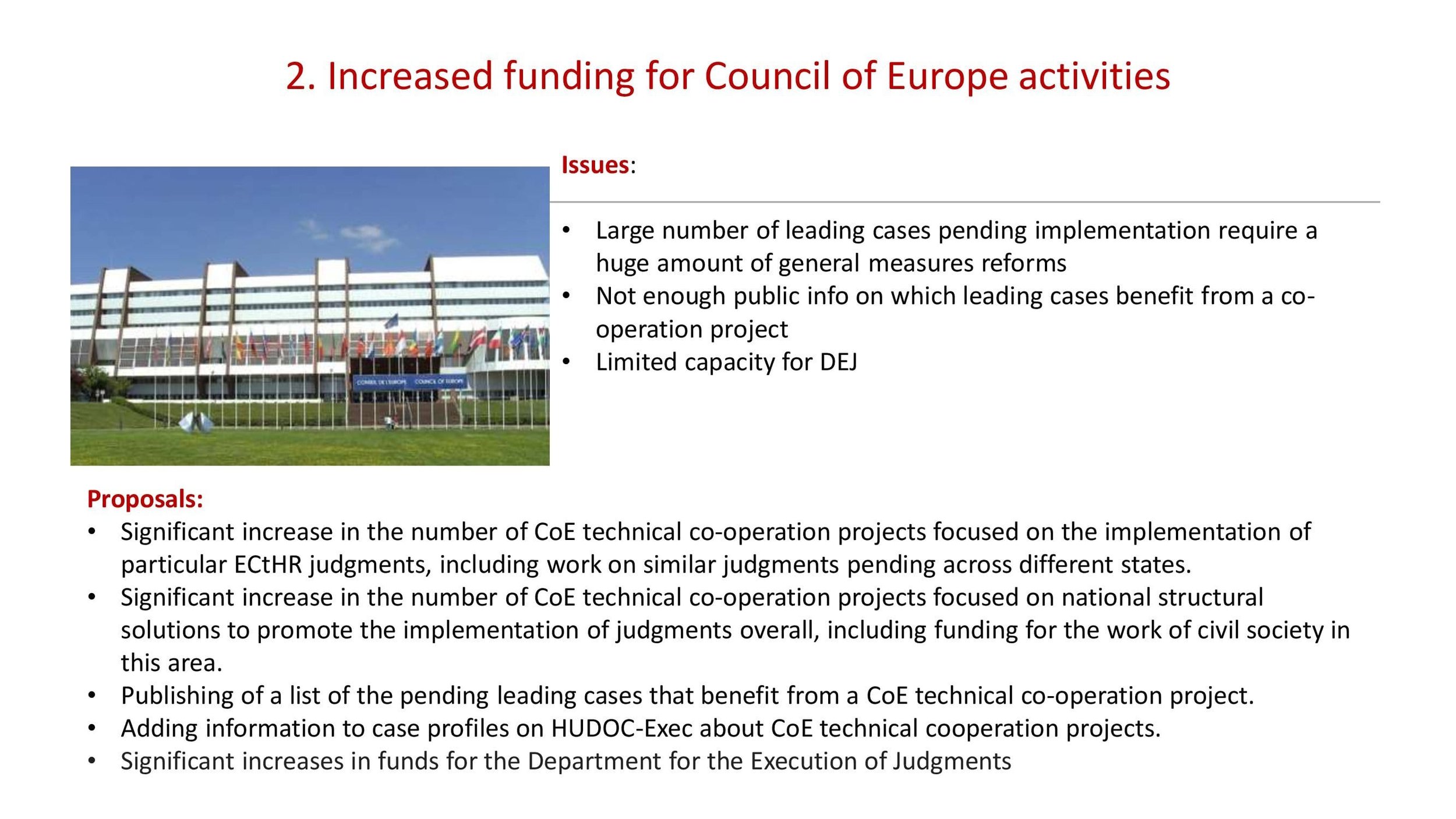

· Significant increases in funds for the Department for the Execution of Judgments;

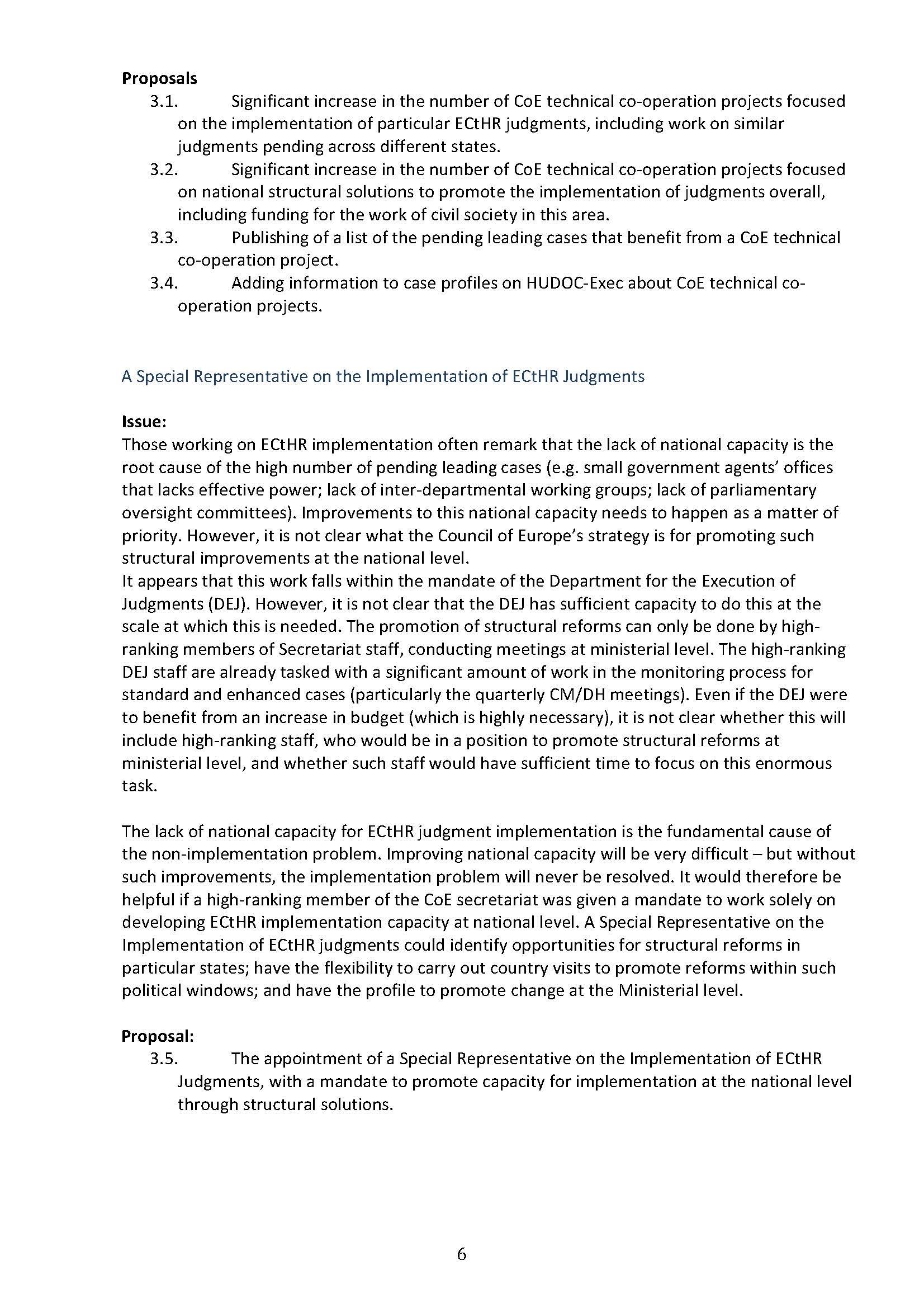

· A significant increase in technical co-operation projects focused on ECtHR implementation;

· A special representative on the implementation of ECtHR judgments;

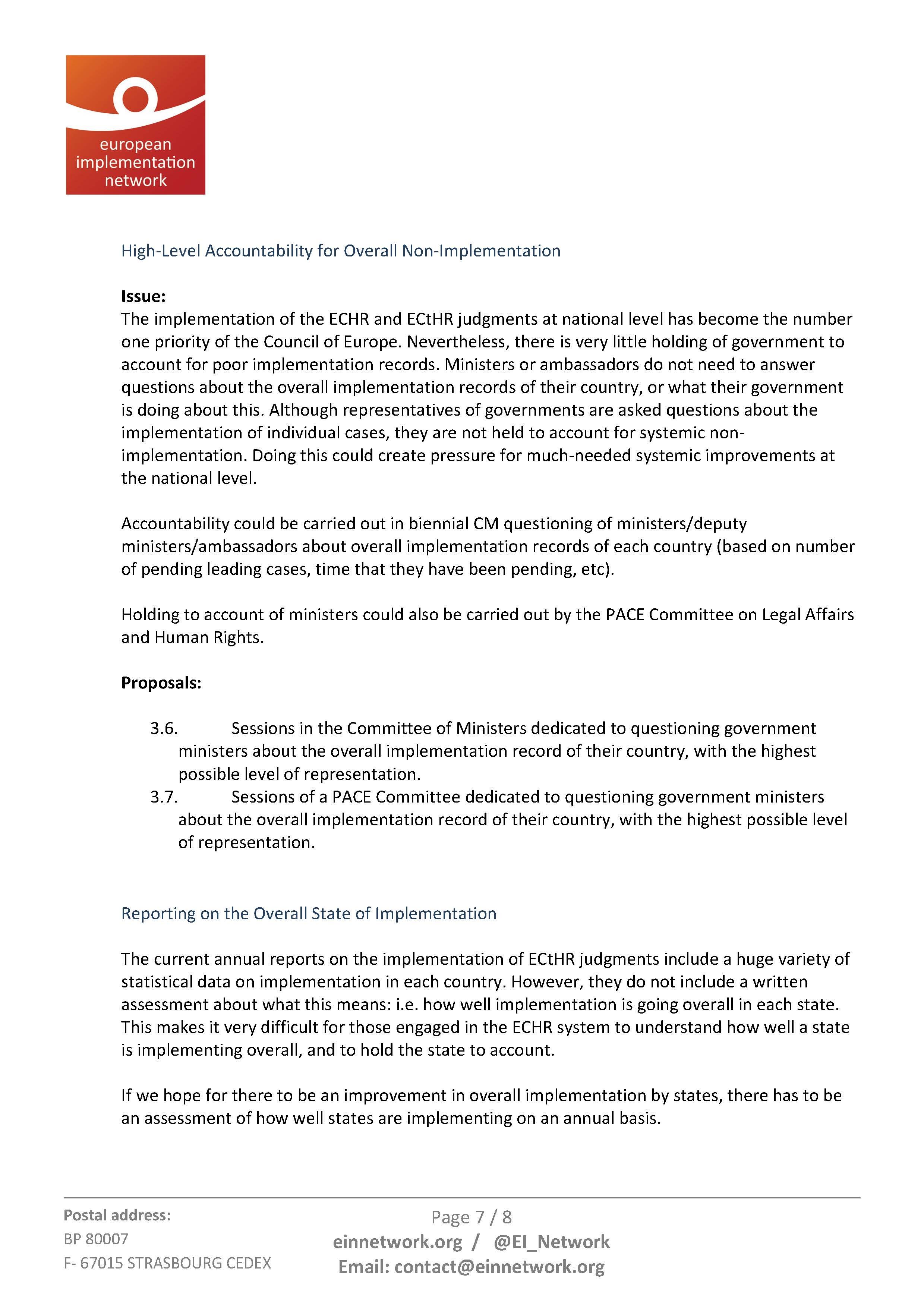

· A new sanction by the Committee of Ministers for continued non-implementation;

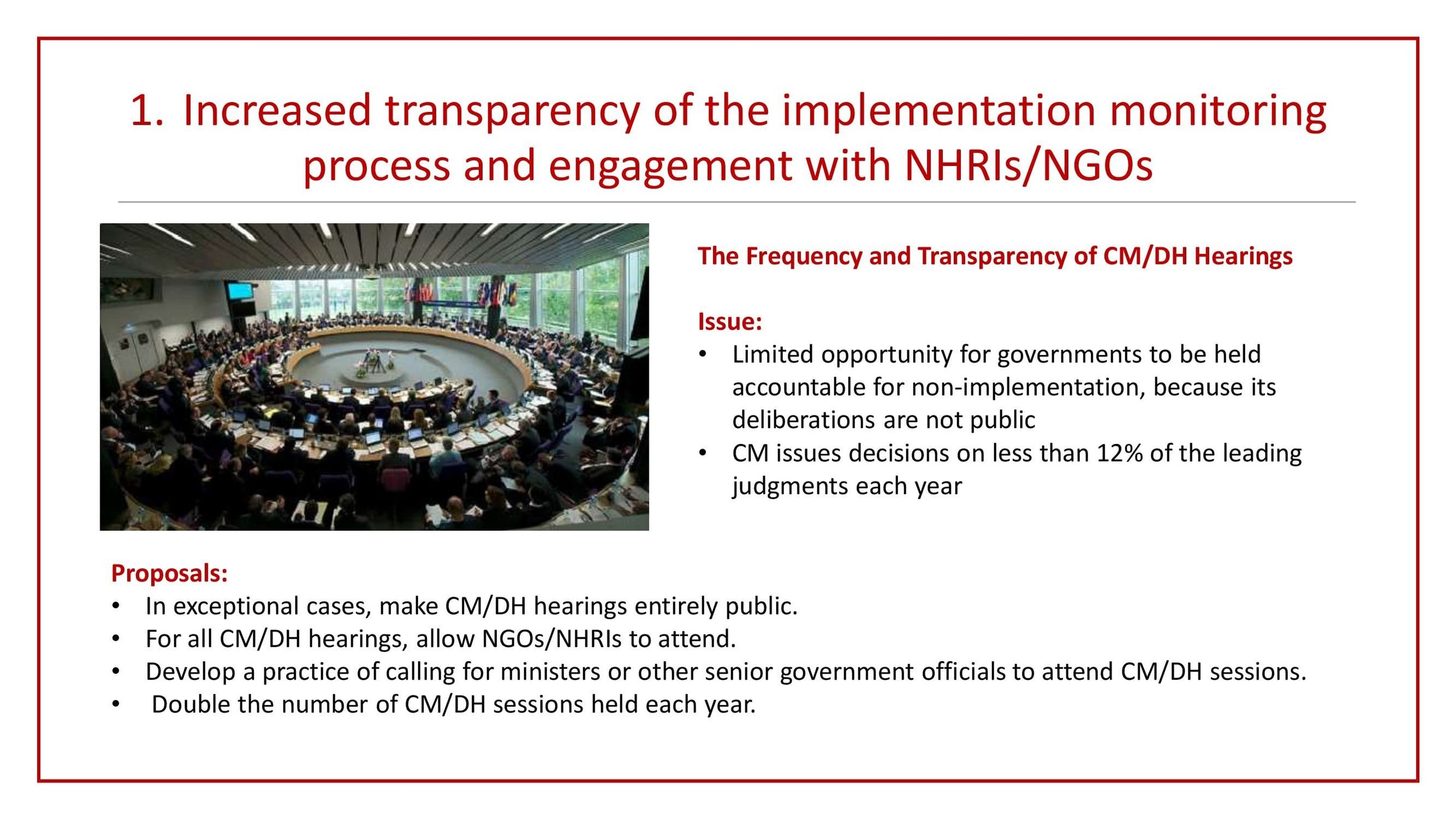

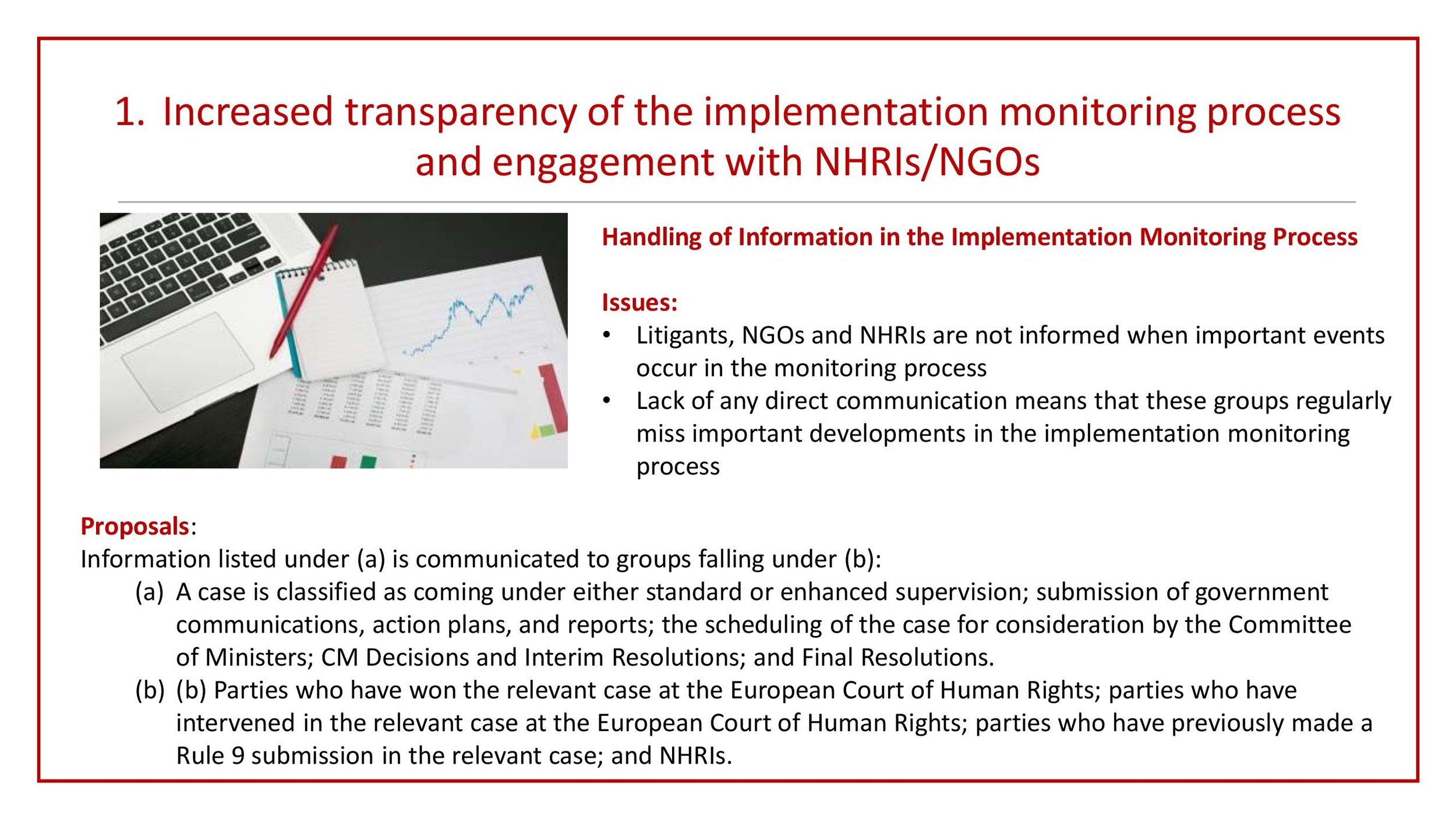

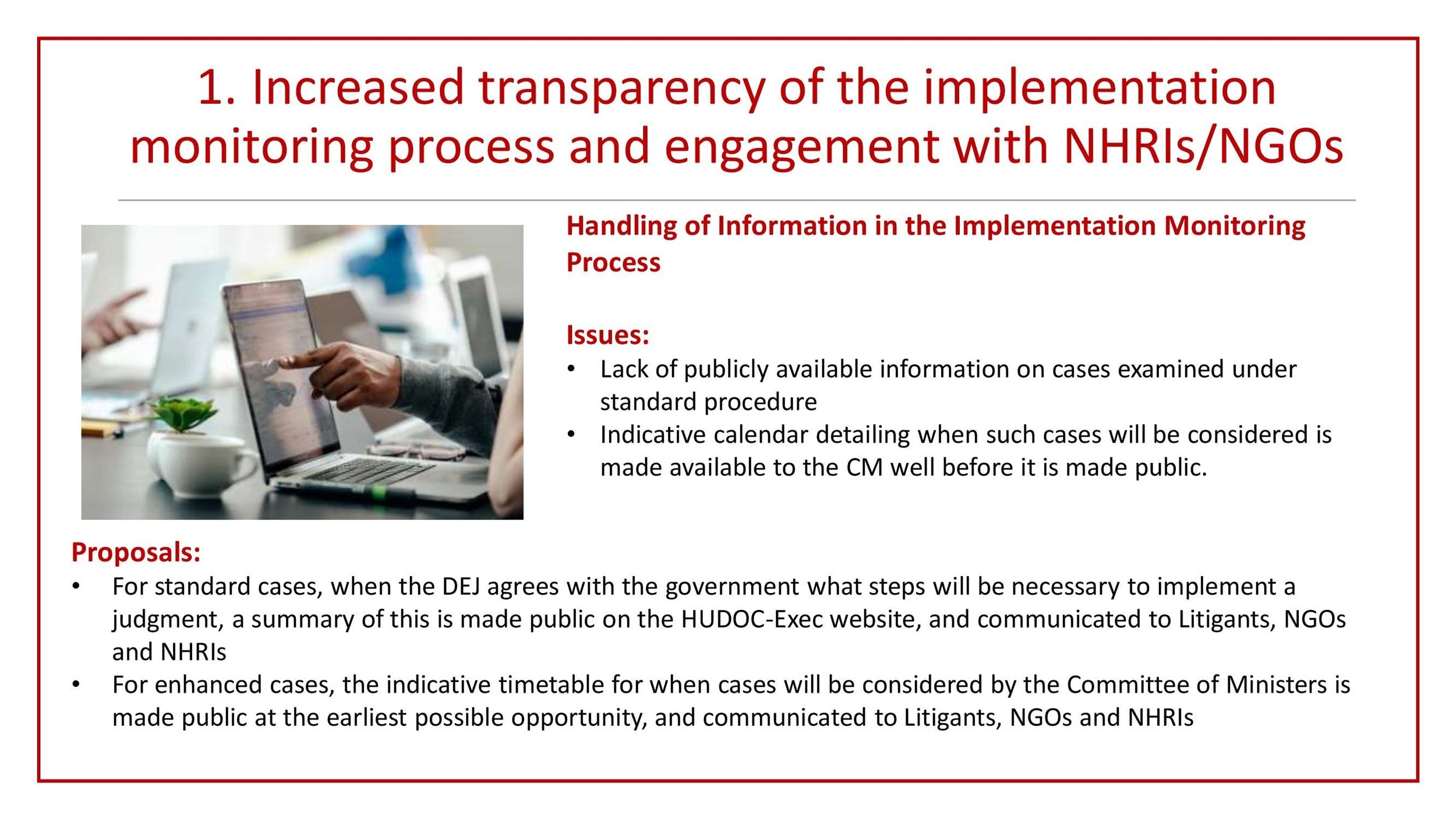

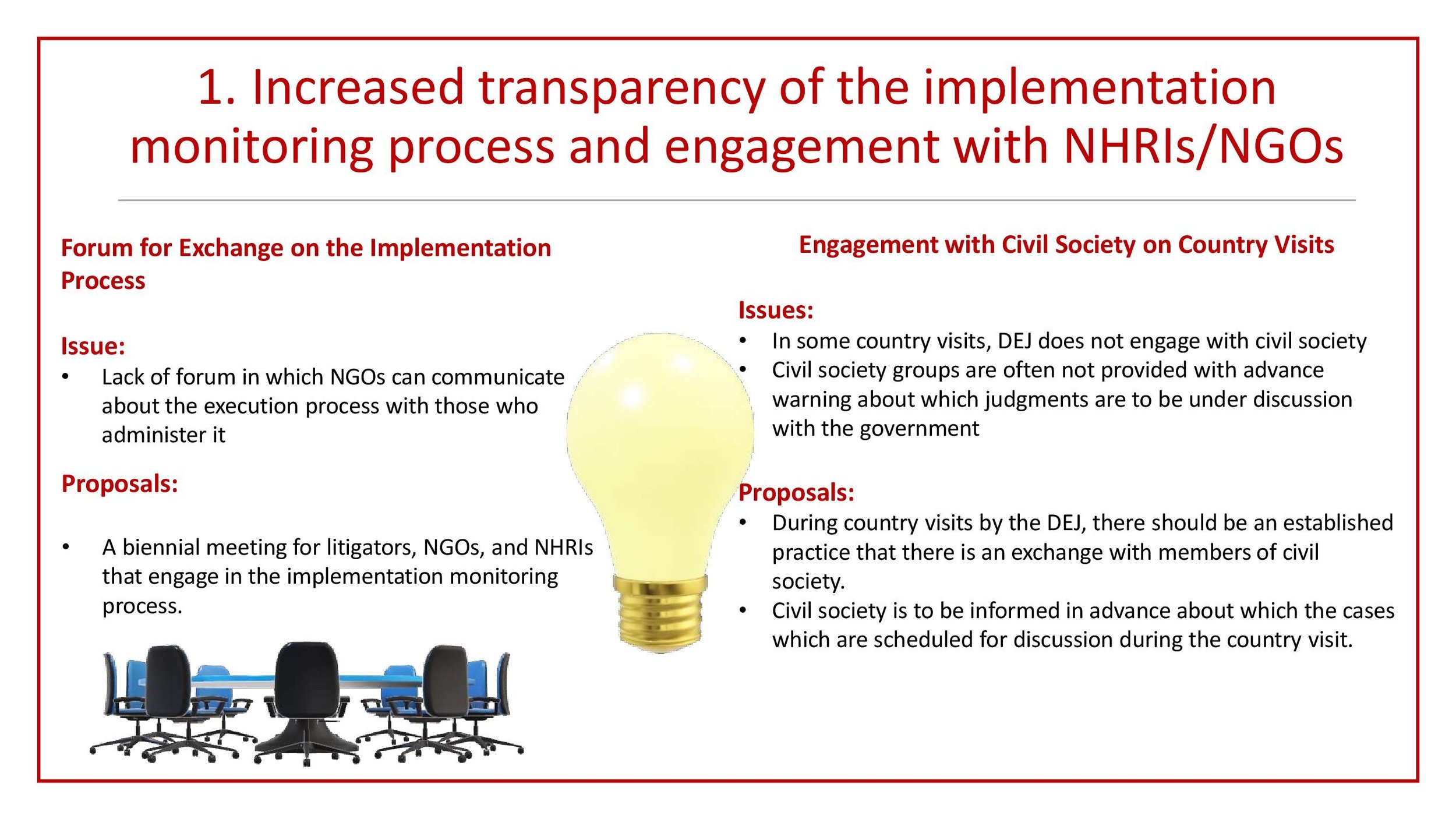

· Increased transparency of the implementation monitoring process and engagement with NHRIs/NGOs; and

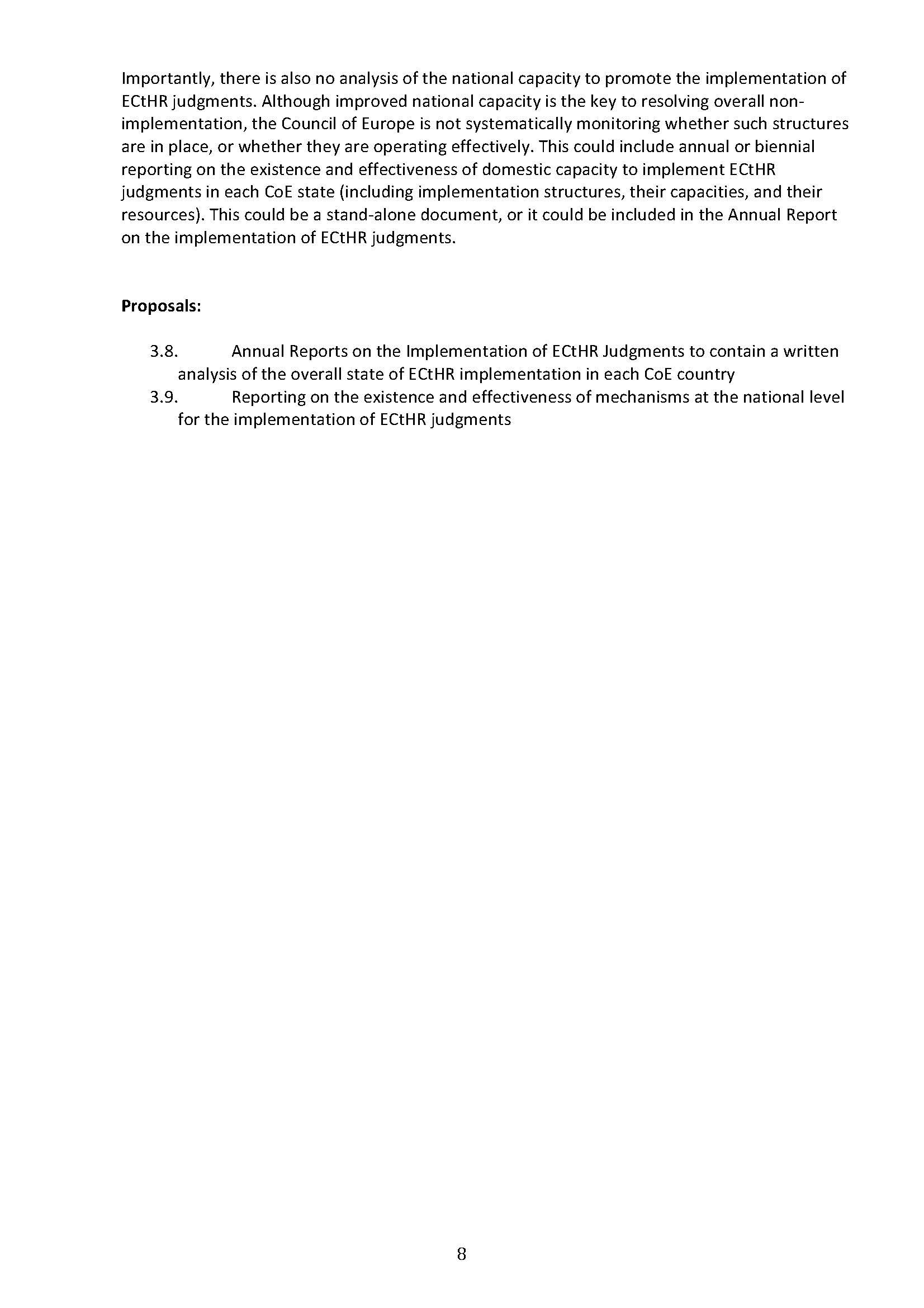

· Annual country-by-country assessments of the state of ECtHR implementation and national capacity in each state.

Any credible strategy would require political will and financial resources commensurate with the scale of the problem.

Effective implementation of the ECtHR’s judgments will reap huge benefits for the protection of human rights, democracy, and the rule of law; the preservation and strengthening of a common European legal space; and ultimately protecting European security by preventing the rise of authoritarianism. Conversely, continued systemic non-implementation presents grave challenges to Europe’s core values.

The European Court of Human Rights is often described as the “jewel in the crown” of the Council of Europe and its protections for human rights, democracy, and the rule of law.

It is time for the Council of Europe to protect this jewel, if it is to be preserved for future generations.

Signed by the EIN Board, composed of:

Chair of EIN Professor Başak Çalı, Co-Director of the Centre for Fundamental Rights, Hertie School of Governance, Berlin

Vice-Chair of EIN Professor Philip Leach, Professor of Human Rights Law at Middlesex University, London

Treasurer of EIN Dr Krassimir Kanev, Director of the Bulgarian Helsinki Committee

Secretary of EIN the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights, represented by Marcin Szwed

Vice Secretary of EIN, Ramute Remezaite, Head of Implementation at the European Human Rights Advocacy Centre

Vivien Brassoi, Legal Director, European Roma Rights Centre, Hungary

Christian De Vos, Director of Research and Investigations, Physicians for Human Rights and Adjunct Assistant Professor of Political Science, Columbia University

Panayote Dimitras, Founder and Spokesperson of the Greek Helsinki Monitor

Ecaterina-Georgiana Gheorghe, Executive Director, Association for the Defence of Human Rights in Romania (APADOR-CH)

Judgment Watch, represented by Professor Malcolm Langford, Professor of Public Law at the University of Oslo

Kristina Todorovic, Attorney at law at the Lawyers’ Committee for Human Rights (YUCOM), Serbia

Discover EIN’s proposals for the work of the Council of Europe on the implementation of judgments of the European Court of Human Rights here.

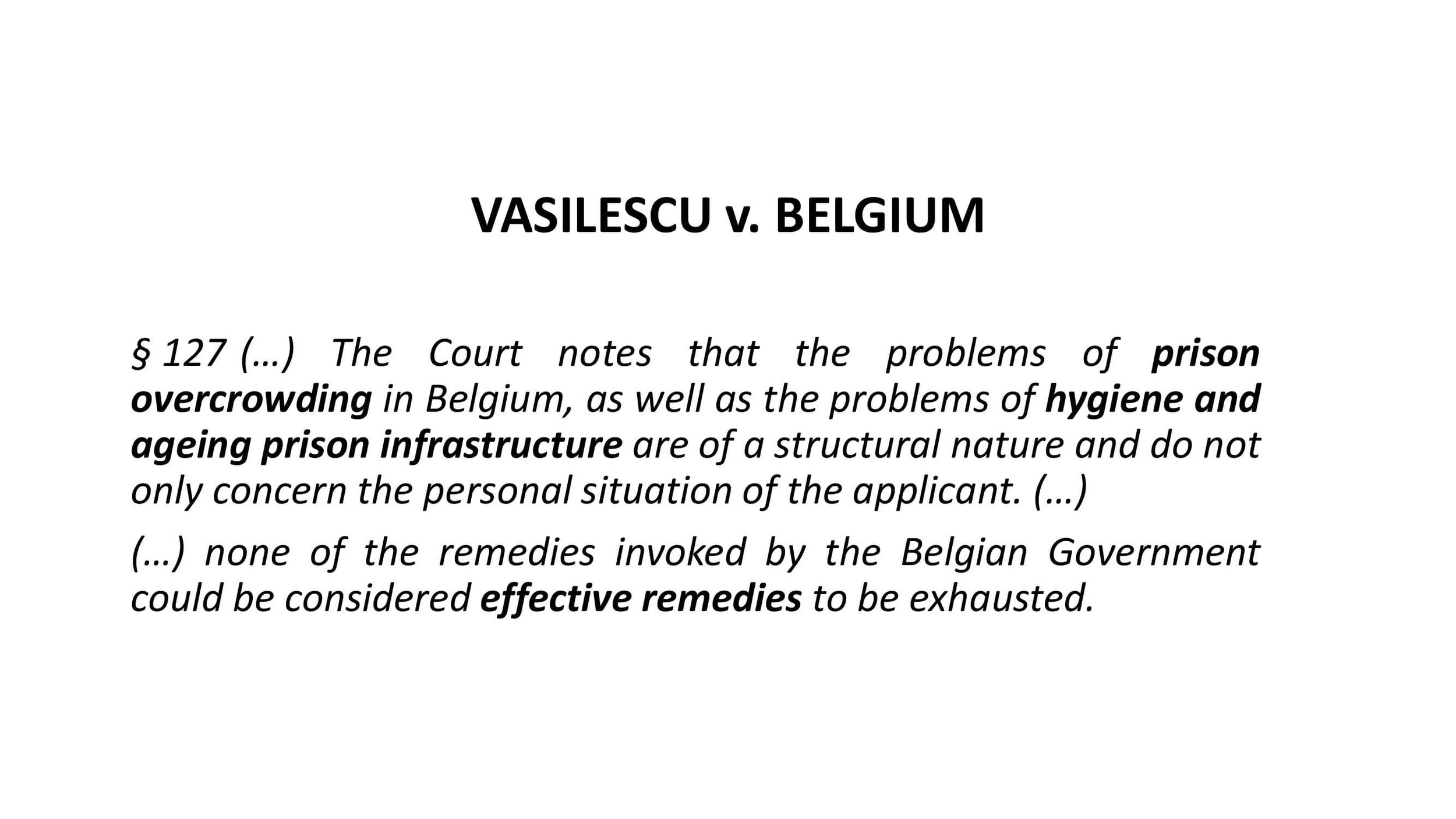

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_1.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312659670-P7UOXBV9F2WE1HBXG8CM/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_1.jpg)

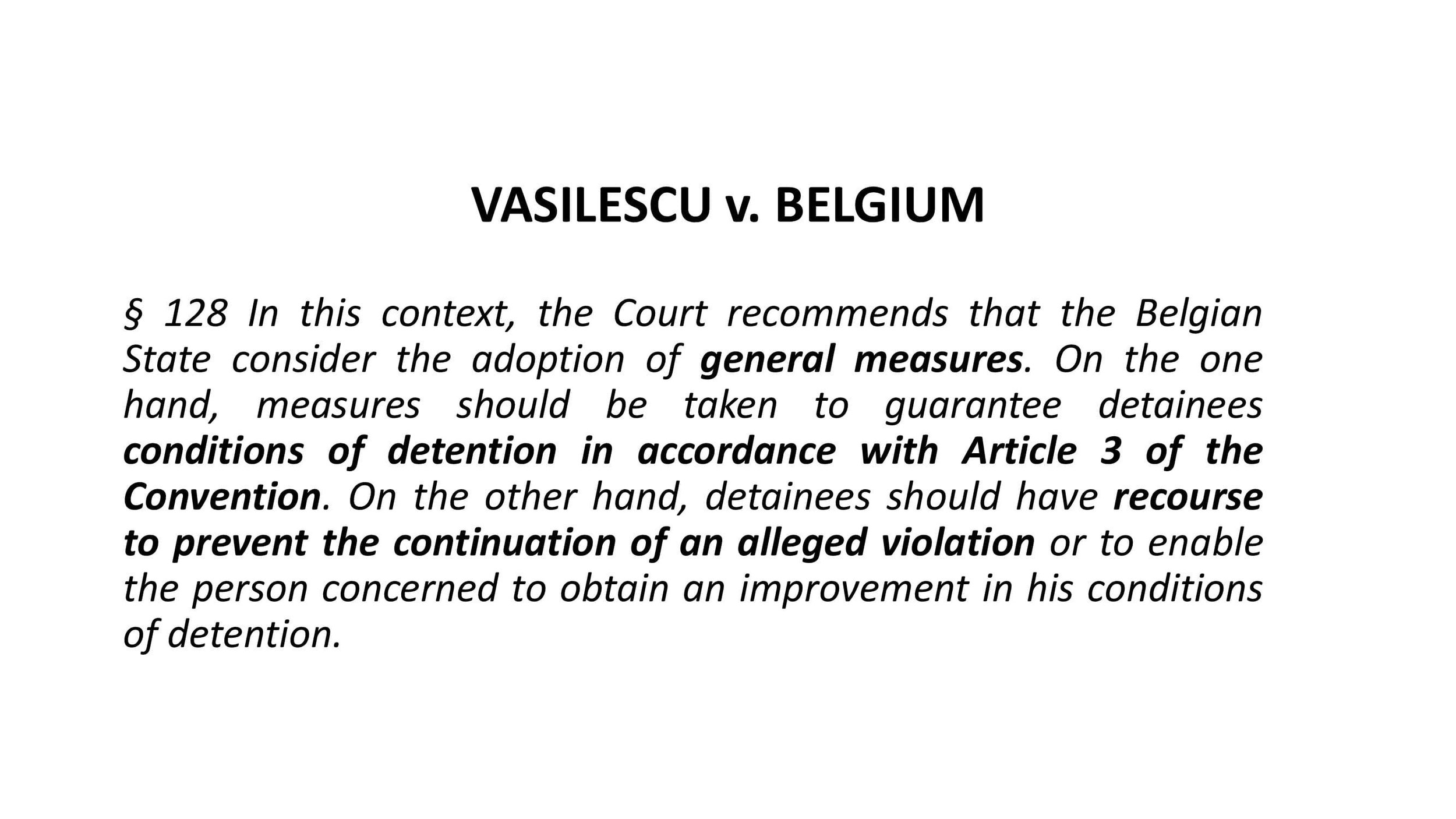

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_2.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312659779-4J3152LHLLE24021SU5U/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_2.jpg)

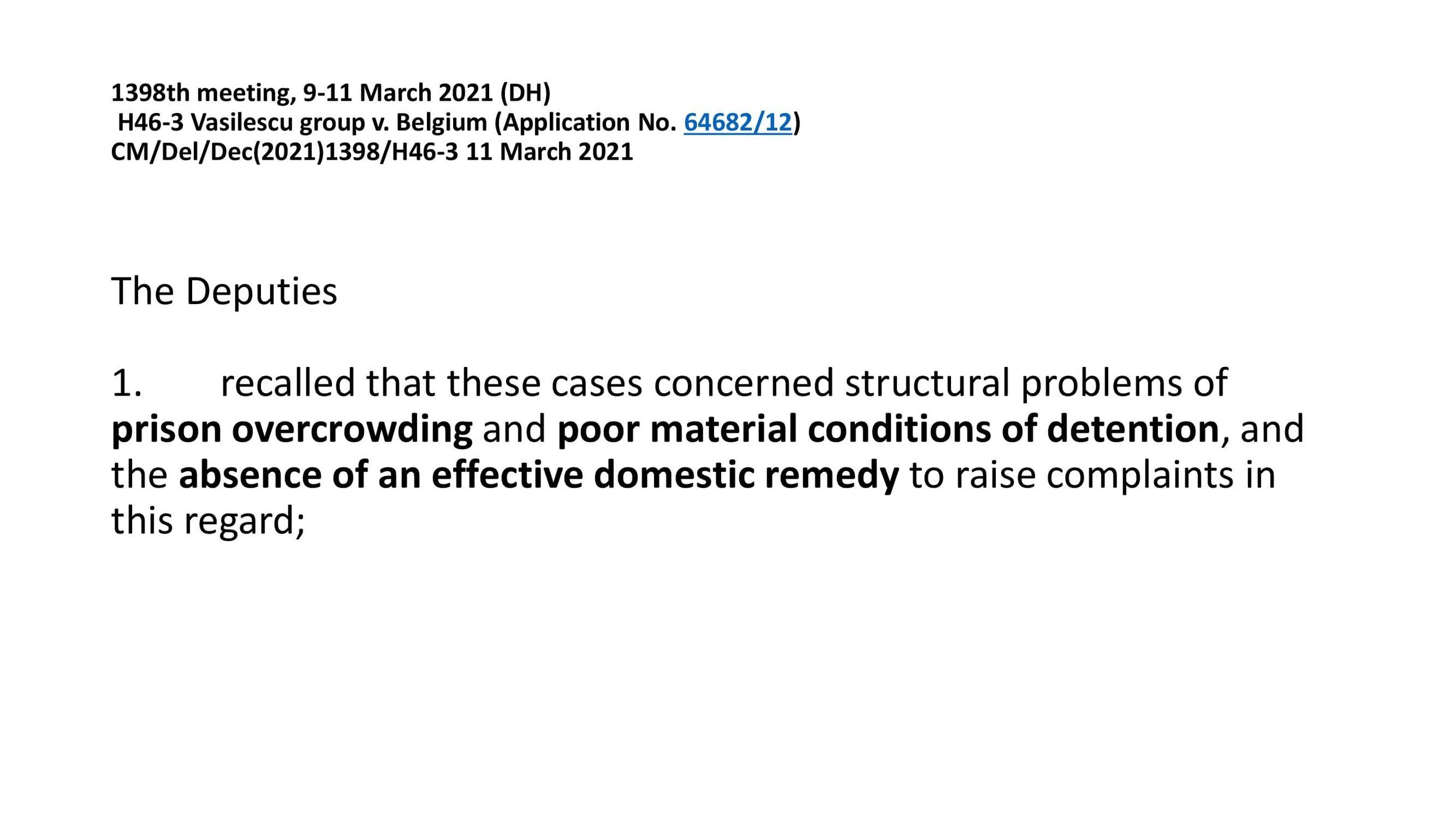

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_3.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312660324-RN6HZ3MVKBSRT2WVD0OA/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_3.jpg)

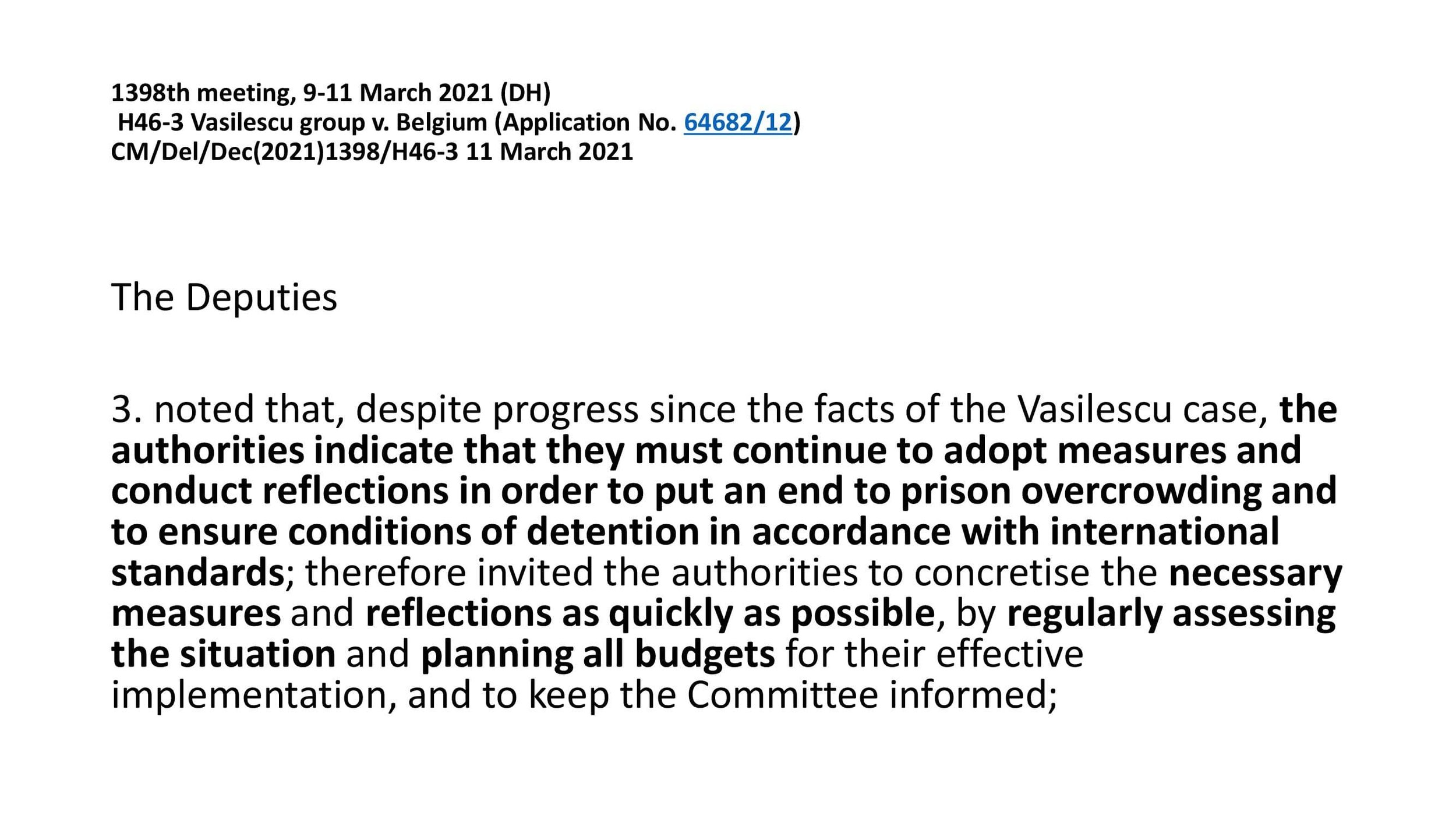

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_4.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312660683-8P9Y0ZMSXTBB8M0B8SMQ/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_4.jpg)

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_5.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312660939-QTS1VE1YMBQ1WGZI677G/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_5.jpg)

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_6.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312661330-KIOW6KFXRU7GNVJ5I648/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_6.jpg)

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_7.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312661753-B7NJLRYLJ6BK9EB0XHS7/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_7.jpg)

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_8.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312661987-EEMHPPEQ0W2IO6R4AOAL/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_8.jpg)

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_9.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312662426-TRVV0MZJ658ZG3WS6VY0/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_9.jpg)

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_10.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312662678-9RW8YABBTHIVCXL1IRG5/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_10.jpg)

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_11.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312663081-732YQ33632AKJV3Q0PQA/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_11.jpg)

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_12.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312663436-CV1T29URTI29P1TH05J4/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_12.jpg)

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_13.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312663712-UXRPIGHNQ5PUEDV8YZFD/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_13.jpg)

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_14.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312664495-8EYGJQ43B8QQS497FYH6/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_14.jpg)

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_15.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312664721-RIWUJ10IWTNE9W4PW1MY/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_15.jpg)

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_16.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312665187-Y5BFI9P331IGWJ9G0DPJ/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_16.jpg)

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_17.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312665540-OED4RWH1JBHRQXXH6WH5/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_17.jpg)

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_18.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312665823-U5XCCRFJ2YF0YAMIMM78/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_18.jpg)

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_19.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312666240-GE4THPOMXFMIQDSK5YJO/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_19.jpg)

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_20.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312666568-0MCJH3IFAUBEP3VEFQK4/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_20.jpg)

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_21.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312666849-488V1UBRD1500S9NBZMB/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_21.jpg)

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_22.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312667194-XOF1I6XM863ED9IWMFM2/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_22.jpg)

![IDvM_Final[43]1024_23.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663312667642-P2KO4231PSVNNJNEY2CL/IDvM_Final%5B43%5D1024_23.jpg)

![20220914_Skendžić and Krznarić group -ENv2[75] - Read-Only-0.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663268133110-9R91RUEBJXBEH9QCQFKW/20220914_Skendz%CC%8Cic%CC%81+and+Krznaric%CC%81+group+-ENv2%5B75%5D+-+Read-Only-0.jpg)

![20220914_Skendžić and Krznarić group -ENv2[75] - Read-Only-1.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663268133177-DPUBS0WHRCFAANBHR1DY/20220914_Skendz%CC%8Cic%CC%81+and+Krznaric%CC%81+group+-ENv2%5B75%5D+-+Read-Only-1.jpg)

![20220914_Skendžić and Krznarić group -ENv2[75] - Read-Only-2.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663268133852-I8AT9N9NG6WKHOETR4VV/20220914_Skendz%CC%8Cic%CC%81+and+Krznaric%CC%81+group+-ENv2%5B75%5D+-+Read-Only-2.jpg)

![20220914_Skendžić and Krznarić group -ENv2[75] - Read-Only-3.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663268133981-6O1EY1HKRI9LHBYLS06D/20220914_Skendz%CC%8Cic%CC%81+and+Krznaric%CC%81+group+-ENv2%5B75%5D+-+Read-Only-3.jpg)

![20220914_Skendžić and Krznarić group -ENv2[75] - Read-Only-4.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663268134683-S08H5T010OC1HGL9S5O2/20220914_Skendz%CC%8Cic%CC%81+and+Krznaric%CC%81+group+-ENv2%5B75%5D+-+Read-Only-4.jpg)

![20220914_Skendžić and Krznarić group -ENv2[75] - Read-Only-5.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663268134800-E57KM91UGFDGFPXLP5LE/20220914_Skendz%CC%8Cic%CC%81+and+Krznaric%CC%81+group+-ENv2%5B75%5D+-+Read-Only-5.jpg)

![20220914_Skendžić and Krznarić group -ENv2[75] - Read-Only-6.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663268135511-LCV7KGZ4LWIZJ6M2TIZV/20220914_Skendz%CC%8Cic%CC%81+and+Krznaric%CC%81+group+-ENv2%5B75%5D+-+Read-Only-6.jpg)

![20220914_Skendžić and Krznarić group -ENv2[75] - Read-Only-7.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663268135551-5GSI4I40224PFKV3NZXQ/20220914_Skendz%CC%8Cic%CC%81+and+Krznaric%CC%81+group+-ENv2%5B75%5D+-+Read-Only-7.jpg)

![20220914_Skendžić and Krznarić group -ENv2[75] - Read-Only-8.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663268136132-2AMGOTLQPD4ZOLXH59O8/20220914_Skendz%CC%8Cic%CC%81+and+Krznaric%CC%81+group+-ENv2%5B75%5D+-+Read-Only-8.jpg)

![20220914_Skendžić and Krznarić group -ENv2[75] - Read-Only-9.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663268136274-SE7MYQZZI7LIT2R188NB/20220914_Skendz%CC%8Cic%CC%81+and+Krznaric%CC%81+group+-ENv2%5B75%5D+-+Read-Only-9.jpg)

![20220914_Skendžić and Krznarić group -ENv2[75] - Read-Only-10.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663268136820-NV18EUVT0R3D2UEVQW8J/20220914_Skendz%CC%8Cic%CC%81+and+Krznaric%CC%81+group+-ENv2%5B75%5D+-+Read-Only-10.jpg)

![20220914_Skendžić and Krznarić group -ENv2[75] - Read-Only-11.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663268136945-BRJRYJ4YQYKVB8ZFCWQI/20220914_Skendz%CC%8Cic%CC%81+and+Krznaric%CC%81+group+-ENv2%5B75%5D+-+Read-Only-11.jpg)

![20220914_Skendžić and Krznarić group -ENv2[75] - Read-Only-12.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663268137456-WG6MXB8L0X9D96PXOLSO/20220914_Skendz%CC%8Cic%CC%81+and+Krznaric%CC%81+group+-ENv2%5B75%5D+-+Read-Only-12.jpg)

![20220914_Skendžić and Krznarić group -ENv2[75] - Read-Only-13.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663268137735-R3YSZMAXEQBQY8F7R5AL/20220914_Skendz%CC%8Cic%CC%81+and+Krznaric%CC%81+group+-ENv2%5B75%5D+-+Read-Only-13.jpg)

![20220914_Skendžić and Krznarić group -ENv2[75] - Read-Only-14.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663268138076-CCDIZHL0WEOJNYLADCC6/20220914_Skendz%CC%8Cic%CC%81+and+Krznaric%CC%81+group+-ENv2%5B75%5D+-+Read-Only-14.jpg)

![20220914_Skendžić and Krznarić group -ENv2[75] - Read-Only-15.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663268138391-RQV9TO0LZVVC875UGR5I/20220914_Skendz%CC%8Cic%CC%81+and+Krznaric%CC%81+group+-ENv2%5B75%5D+-+Read-Only-15.jpg)

![20220914_Skendžić and Krznarić group -ENv2[75] - Read-Only-16.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663268138760-6U8RR746CQ5IQMYV8KC3/20220914_Skendz%CC%8Cic%CC%81+and+Krznaric%CC%81+group+-ENv2%5B75%5D+-+Read-Only-16.jpg)

![20220914_Skendžić and Krznarić group -ENv2[75] - Read-Only-17.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663268139051-6WUW67F0GSYLLO64S8K8/20220914_Skendz%CC%8Cic%CC%81+and+Krznaric%CC%81+group+-ENv2%5B75%5D+-+Read-Only-17.jpg)

![20220914_Skendžić and Krznarić group -ENv2[75] - Read-Only-18.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663268139697-3DWKKQFU4G3JYT6L6BQQ/20220914_Skendz%CC%8Cic%CC%81+and+Krznaric%CC%81+group+-ENv2%5B75%5D+-+Read-Only-18.jpg)

![20220914_Skendžić and Krznarić group -ENv2[75] - Read-Only-19.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663268139871-ZDPMQCSRPQ37O8N64KD1/20220914_Skendz%CC%8Cic%CC%81+and+Krznaric%CC%81+group+-ENv2%5B75%5D+-+Read-Only-19.jpg)

![20220914_Skendžić and Krznarić group -ENv2[75] - Read-Only-20.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663268140267-P9FXP7JAFPS23TQBEB3D/20220914_Skendz%CC%8Cic%CC%81+and+Krznaric%CC%81+group+-ENv2%5B75%5D+-+Read-Only-20.jpg)

![Ilias and Ahmed (1)[85]-0.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663267898413-VZE6ITQEX11X2K6JARV9/Ilias+and+Ahmed+%281%29%5B85%5D-0.jpg)

![Ilias and Ahmed (1)[85]-1.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663267898428-1UIXENO8HAHMBJQJXEIM/Ilias+and+Ahmed+%281%29%5B85%5D-1.jpg)

![Ilias and Ahmed (1)[85]-2.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663267899064-VP24SP9JG0FWDY8N04GC/Ilias+and+Ahmed+%281%29%5B85%5D-2.jpg)

![Ilias and Ahmed (1)[85]-3.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663267899395-1P1CAA08DGIIJ0PVVFP7/Ilias+and+Ahmed+%281%29%5B85%5D-3.jpg)

![Ilias and Ahmed (1)[85]-4.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663267900059-X59B8JEUB8EOLVK6GDN1/Ilias+and+Ahmed+%281%29%5B85%5D-4.jpg)

![Ilias and Ahmed (1)[85]-5.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663267900175-8BKM28CHB4ASYXNCERX6/Ilias+and+Ahmed+%281%29%5B85%5D-5.jpg)

![Ilias and Ahmed (1)[85]-6.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663267900982-CWUX0UIV87Z25T15VCTM/Ilias+and+Ahmed+%281%29%5B85%5D-6.jpg)

![Ilias and Ahmed (1)[85]-7.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663267901167-M03GBSVU0IB7V7YJQ40H/Ilias+and+Ahmed+%281%29%5B85%5D-7.jpg)

![Ilias and Ahmed (1)[85]-8.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663267901810-7KV7LQJLTJCN1KSBYA1H/Ilias+and+Ahmed+%281%29%5B85%5D-8.jpg)

![Ilias and Ahmed (1)[85]-9.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663267901885-S5HVDUD90YDBEJMJSGNN/Ilias+and+Ahmed+%281%29%5B85%5D-9.jpg)

![Ilias and Ahmed (1)[85]-10.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663267902543-KQ4BQ17CWEJ03ZS5UNKR/Ilias+and+Ahmed+%281%29%5B85%5D-10.jpg)

![Ilias and Ahmed (1)[85]-11.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663267902685-1U6ZCJ3I4B335QESMJFN/Ilias+and+Ahmed+%281%29%5B85%5D-11.jpg)

![Ilias and Ahmed (1)[85]-12.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663267903327-NYD1YOQIK22WUYSG3S05/Ilias+and+Ahmed+%281%29%5B85%5D-12.jpg)

![Ilias and Ahmed (1)[85]-13.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663267903470-YPGXCG5NF89S4QIWX7IC/Ilias+and+Ahmed+%281%29%5B85%5D-13.jpg)

![Ilias and Ahmed (1)[85]-14.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663267904014-6K4RT9RXDYYA4BE149VG/Ilias+and+Ahmed+%281%29%5B85%5D-14.jpg)

![Ilias and Ahmed (1)[85]-15.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663267904186-3AUU56MWNTT7CCG1YP6D/Ilias+and+Ahmed+%281%29%5B85%5D-15.jpg)

![Demirtaş - CoM briefing 16.09.22[12] - Read-Only-0.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663270546758-8MNOPZMT9NDT581P6ABM/Demirtas%CC%A7+-+CoM+briefing+16.09.22%5B12%5D+-+Read-Only-0.jpg)

![Demirtaş - CoM briefing 16.09.22[12] - Read-Only-1.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663270547027-EFNJQWCAWYSHIE7B6F66/Demirtas%CC%A7+-+CoM+briefing+16.09.22%5B12%5D+-+Read-Only-1.jpg)

![Demirtaş - CoM briefing 16.09.22[12] - Read-Only-2.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663270547811-MQXY9VGBRKDSAO5V5O3I/Demirtas%CC%A7+-+CoM+briefing+16.09.22%5B12%5D+-+Read-Only-2.jpg)

![Demirtaş - CoM briefing 16.09.22[12] - Read-Only-3.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663270547915-J6FAYNVIY7V23B5X2JJG/Demirtas%CC%A7+-+CoM+briefing+16.09.22%5B12%5D+-+Read-Only-3.jpg)

![Demirtaş - CoM briefing 16.09.22[12] - Read-Only-4.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663270548597-POCBJXTOPWO5M8TOCANB/Demirtas%CC%A7+-+CoM+briefing+16.09.22%5B12%5D+-+Read-Only-4.jpg)

![Demirtaş - CoM briefing 16.09.22[12] - Read-Only-5.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663270548813-FZLM30NCY36PJ65ZMFCS/Demirtas%CC%A7+-+CoM+briefing+16.09.22%5B12%5D+-+Read-Only-5.jpg)

![Demirtaş - CoM briefing 16.09.22[12] - Read-Only-6.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55815c4fe4b077ee5306577f/1663270549322-B30ODKL3WS1H9MMX30NT/Demirtas%CC%A7+-+CoM+briefing+16.09.22%5B12%5D+-+Read-Only-6.jpg)