There is a serious humanitarian problem with regard to the respect and protection of the rights of persons with mental disabilities living in institutional settings in Romania. This blog argues that the only effective way to address the problems identified in these judgments is through a human rights-based approach to disability, which includes the creation of proper community-based care services available for persons with disabilities, and de-institutionalization. This is required by the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN CRPD). However, in previous instances concerning similar issues, the Committee of Ministers has encouraged the creation of “medical residential centers” and the direction of a ‘deinstitutionalization’ strategy in Bulgaria which is faulty. The latter has been highly criticized for being contrary to the UN CRPD, as it moves people from large institutions to smaller buildings. This approach is both unnecessary and harmful. The Committee of Ministers should take into account the human-rights based approach prescribed by the UN CRPD in such cases, in order to ensure the development of effective long-term solutions to these systemic problems.

A serious, invisible humanitarian issue: persons with disabilities in mental health institutions

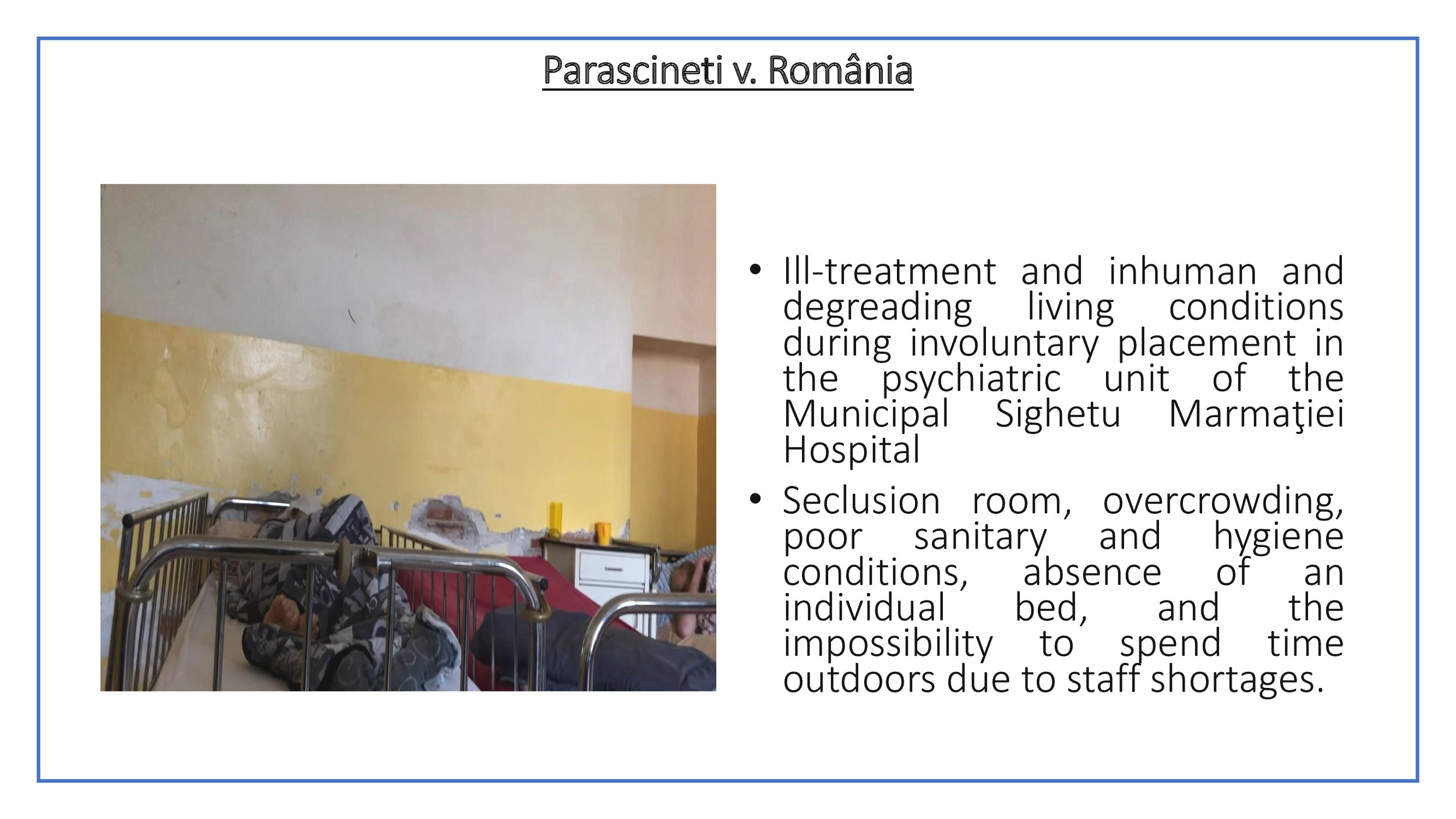

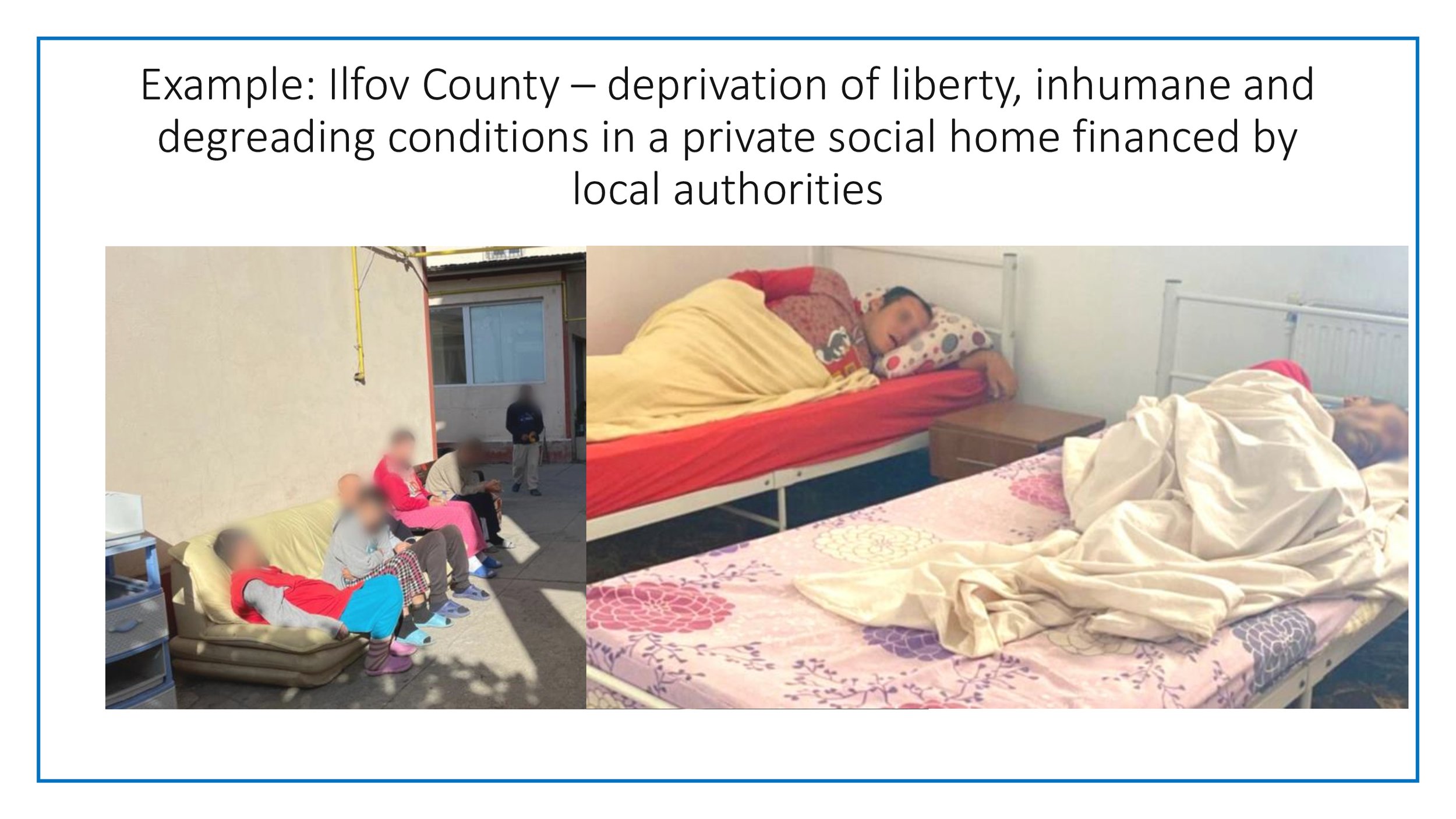

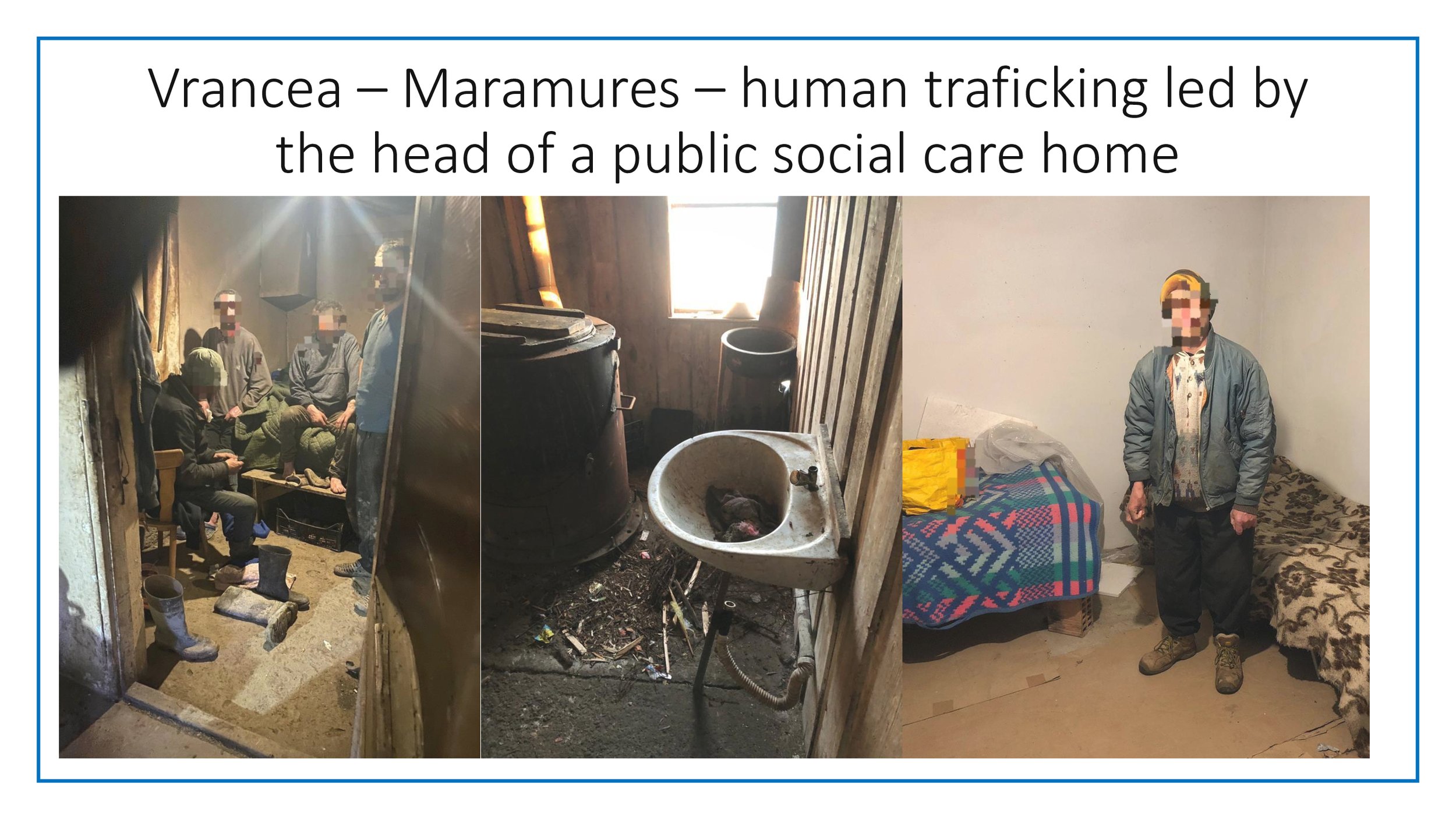

Persons with mental disabilities living in institutional settings in Romania do not have sufficient access to justice to lodge numerous (or even few) applications before the Court, although the human rights violations they face are systematic, wide-ranging, and affect approx. 30 000 people in Romania[i]. They are subjected to ill-treatment, medical neglect, and abuse; they live in overcrowded, poor material conditions of detention. They are placed in institutions by their legal guardians or the state, with whom they are often in a conflict of interest or have never met. When they are voluntarily committed, it is mainly due to a lack of alternative options in the community. Even if they want to leave mental health institutions, they are pressured and manipulated to remain. They are unable or afraid to complain, as they are fully dependent on the staff and management of the institutions where they are placed. Nils Muiznieks, former Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, in his 2014 address to the PACE Committee on Equality and Non-Discrimination explained: „Many who could otherwise function in the community without a great deal of support have become unable or afraid to leave these institutions, because they have known nothing else” and this pattern “cultivates a feeling of helplessness; (…) erodes one’s confidence in one’s ability to make choices; (…) deprive(s) people of life experiences and skills needed to build up autonomy and identity”.

When supervising and implementing these judgments, consideration must be given to this vicious circle which defines life in mental health institutions[ii], and the web of underlying shortcomings which help cause it.

The need for a human-rights based approach to disability: community-based living and treatment alternatives as prerequisites to effective long-term solutions

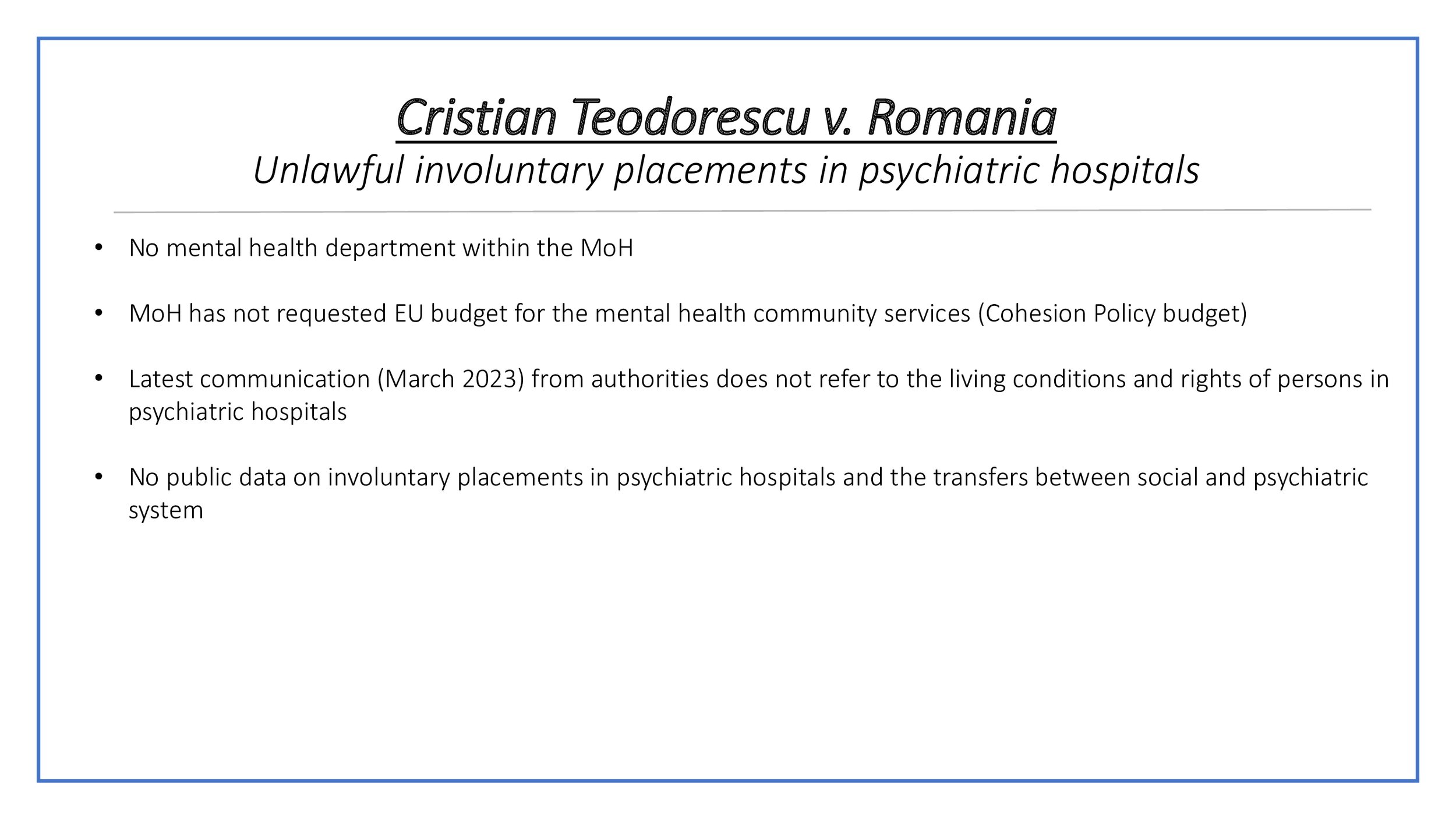

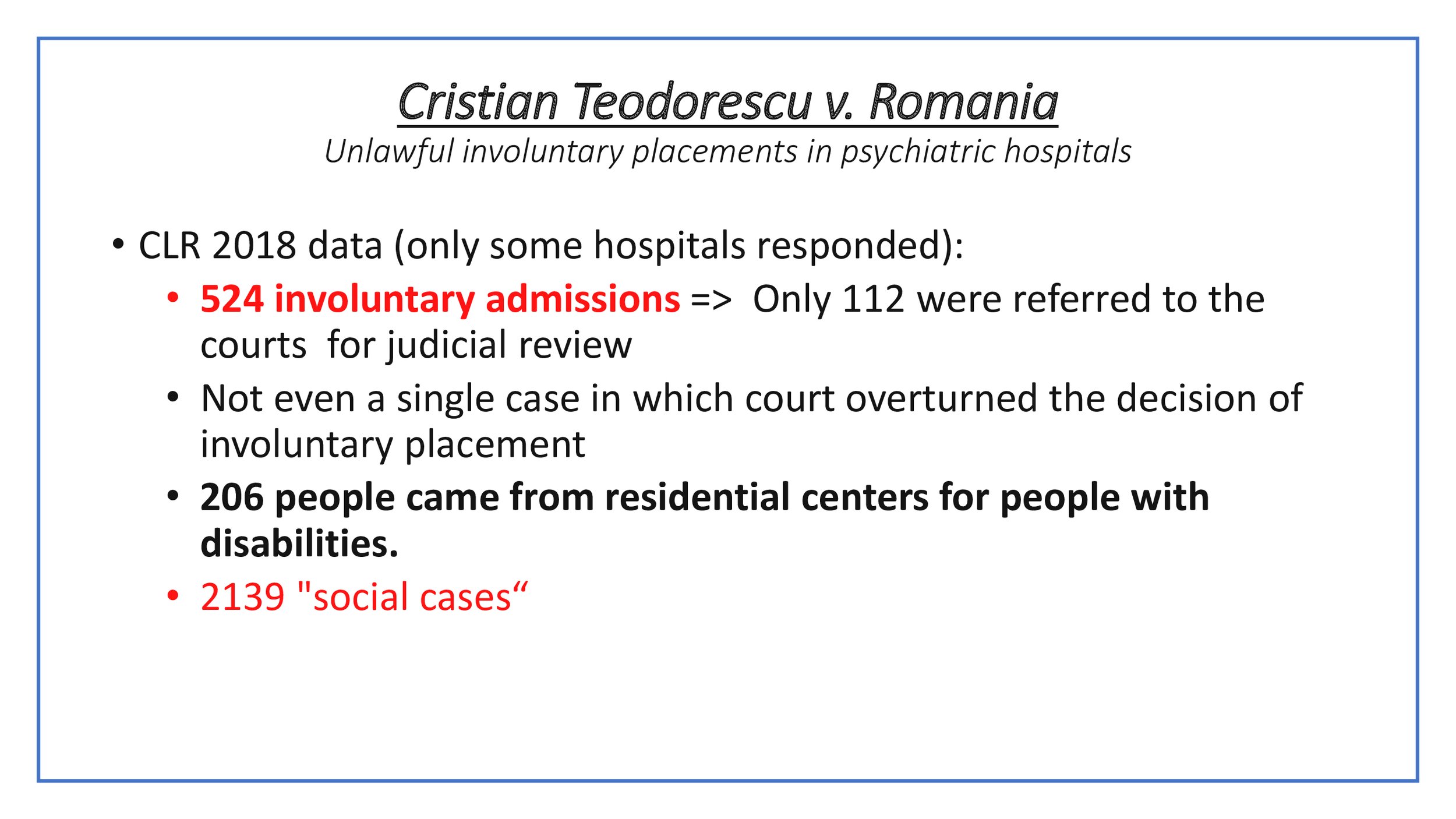

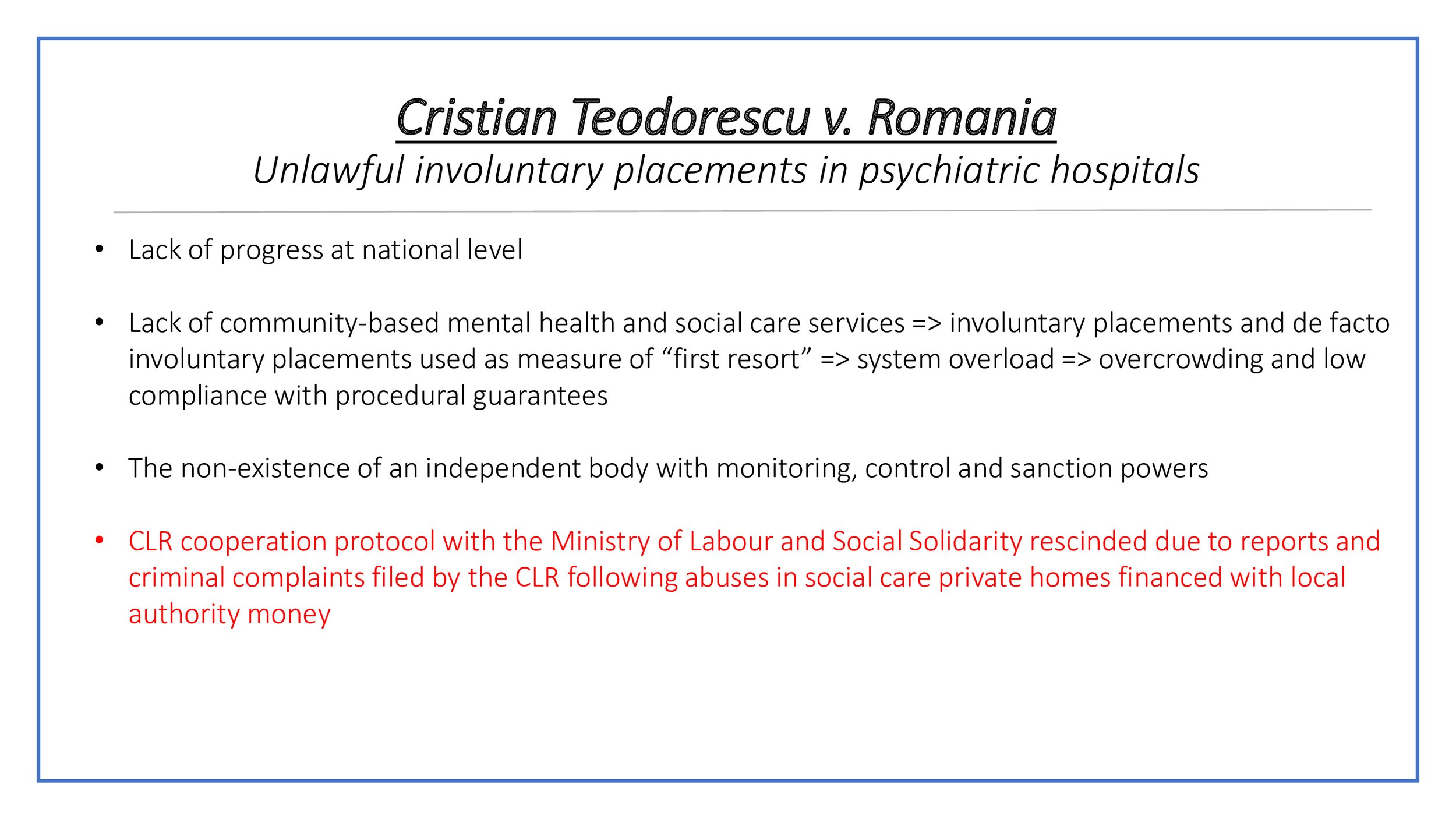

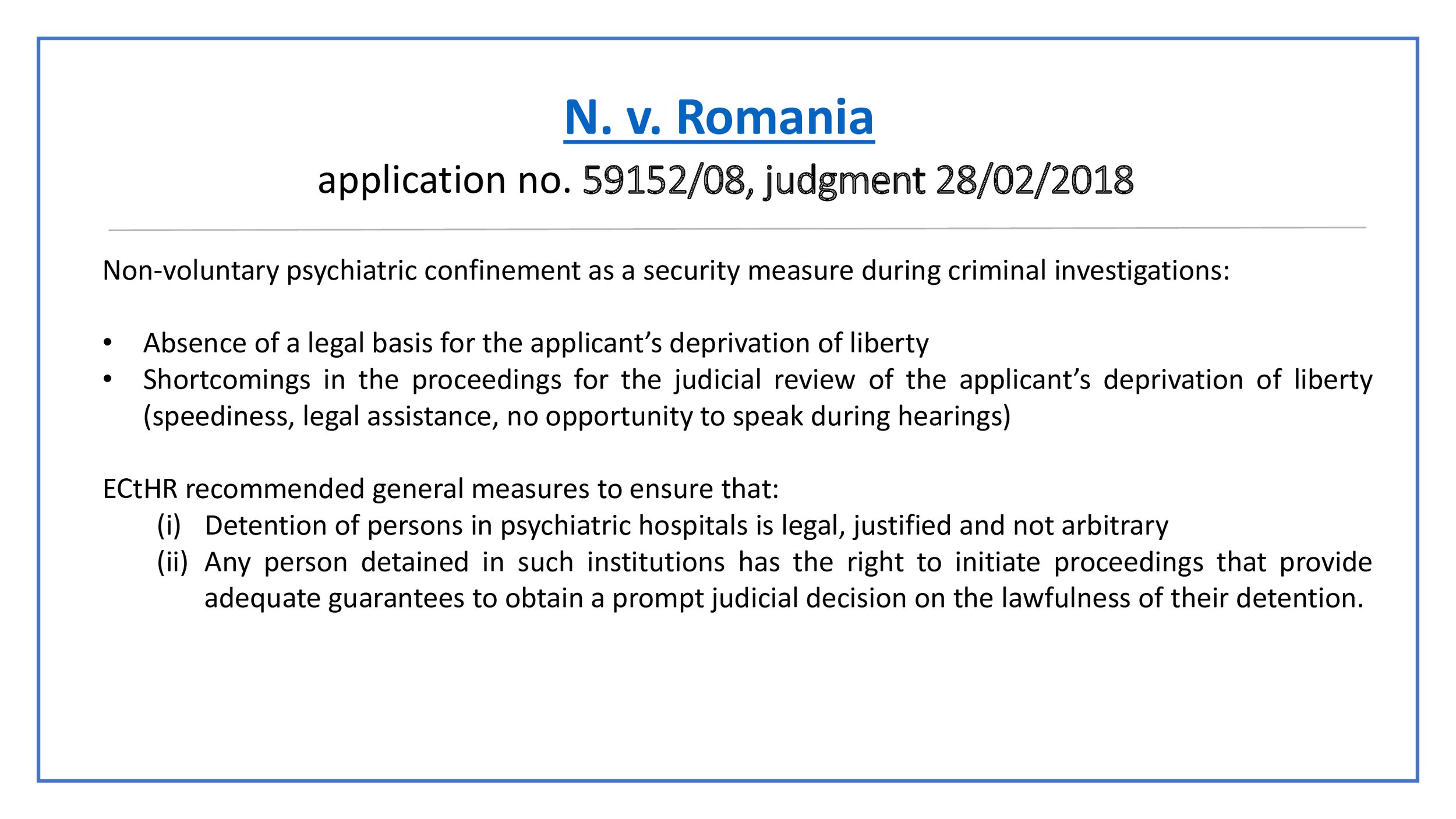

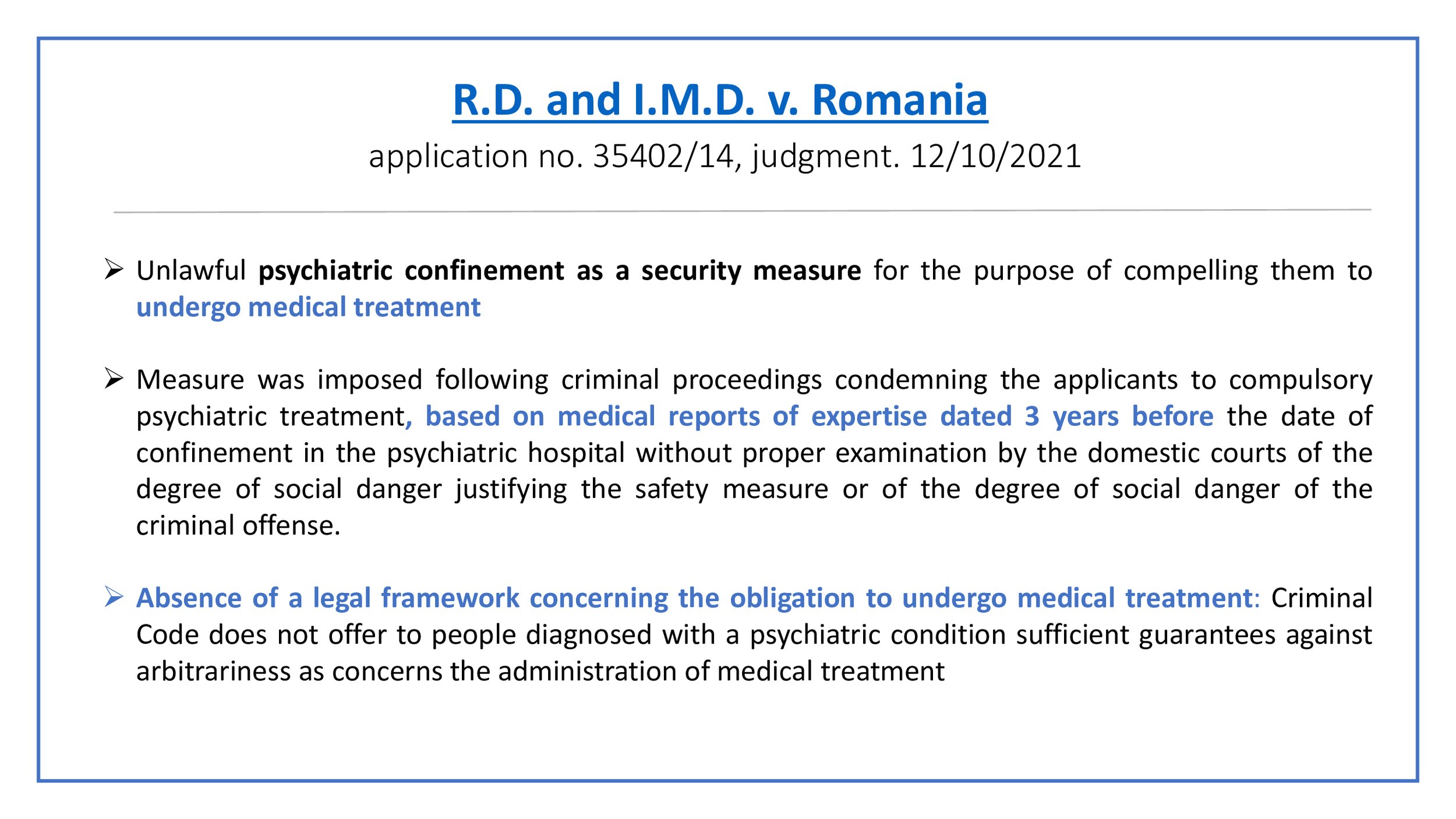

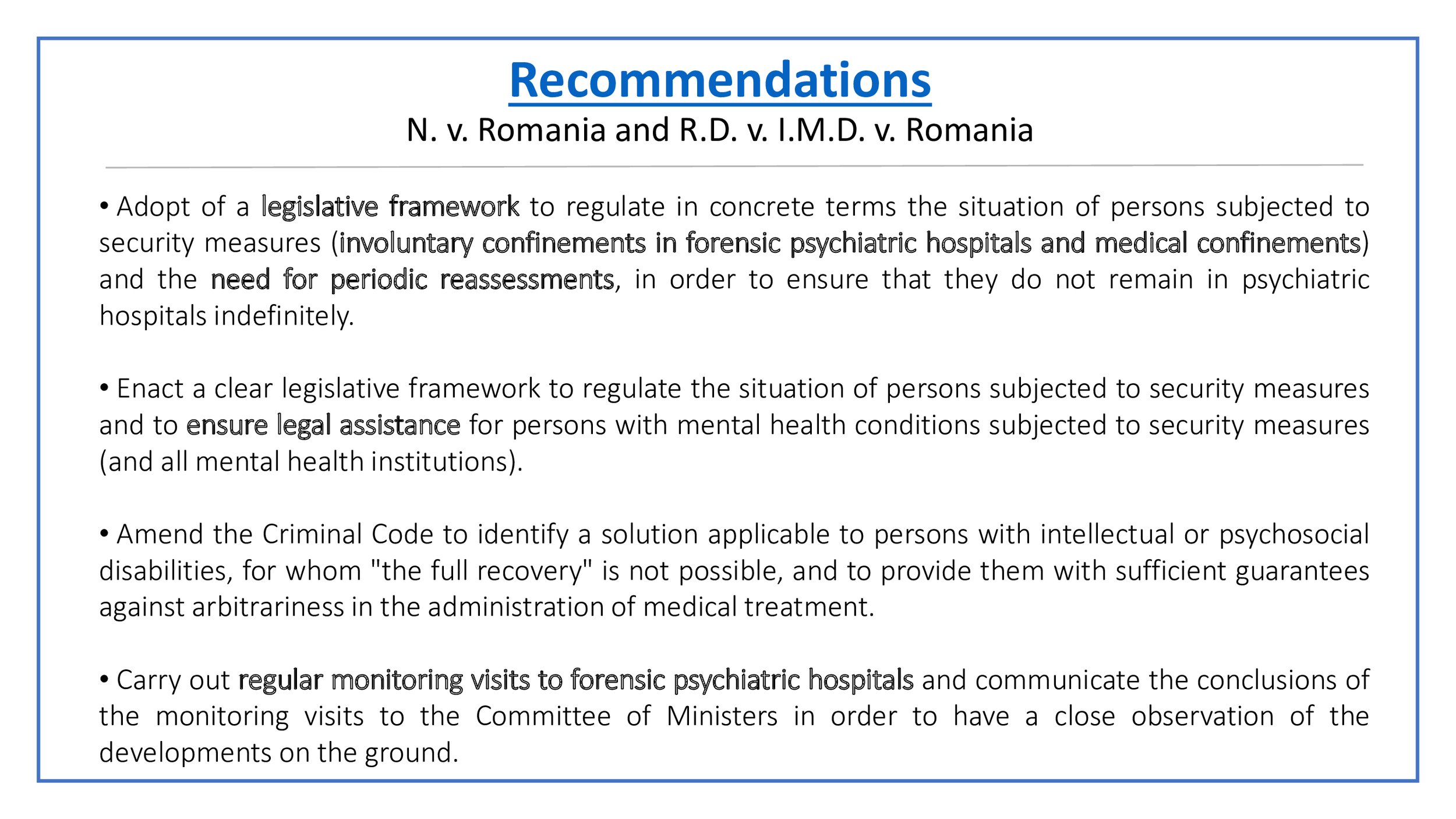

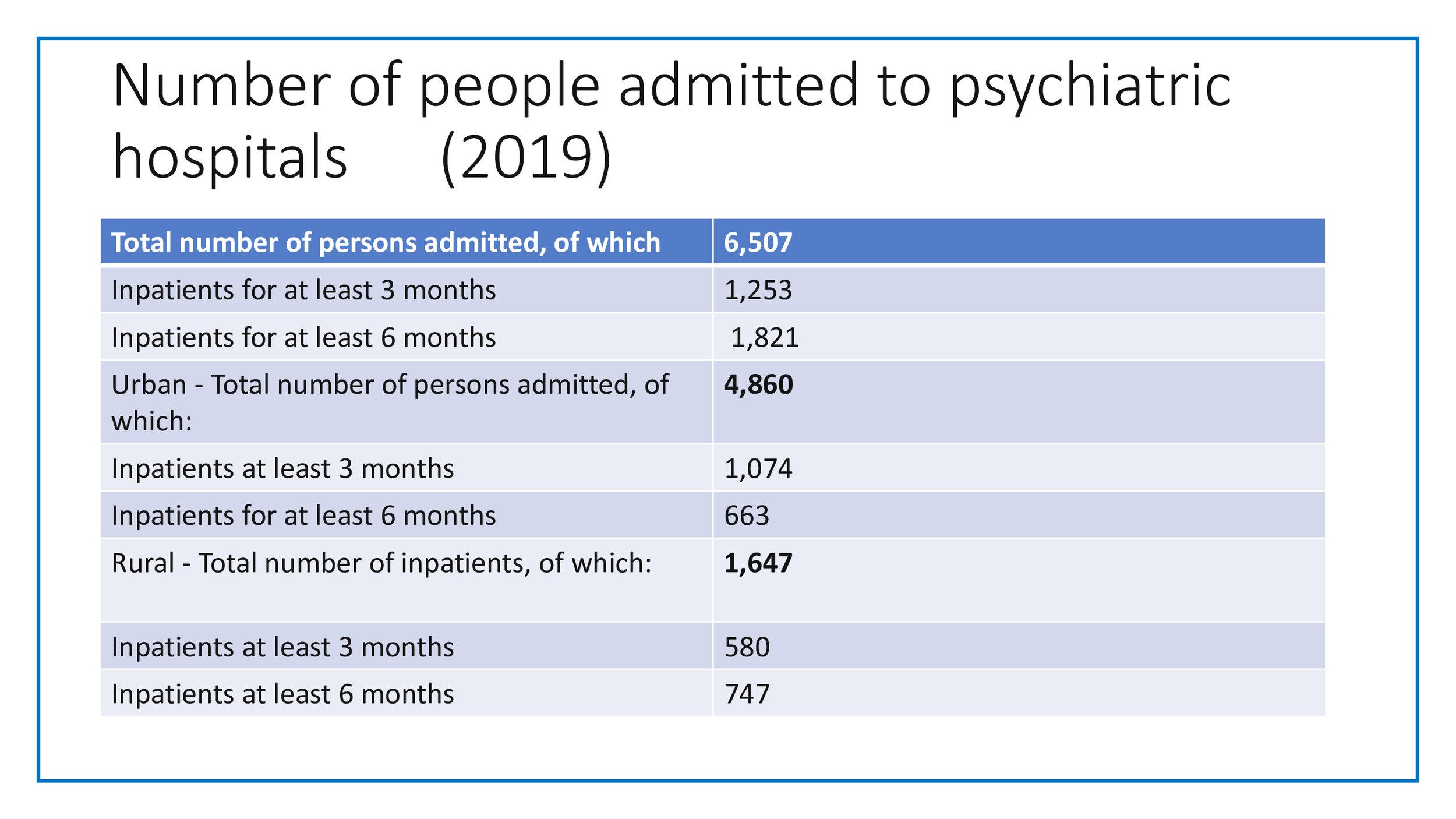

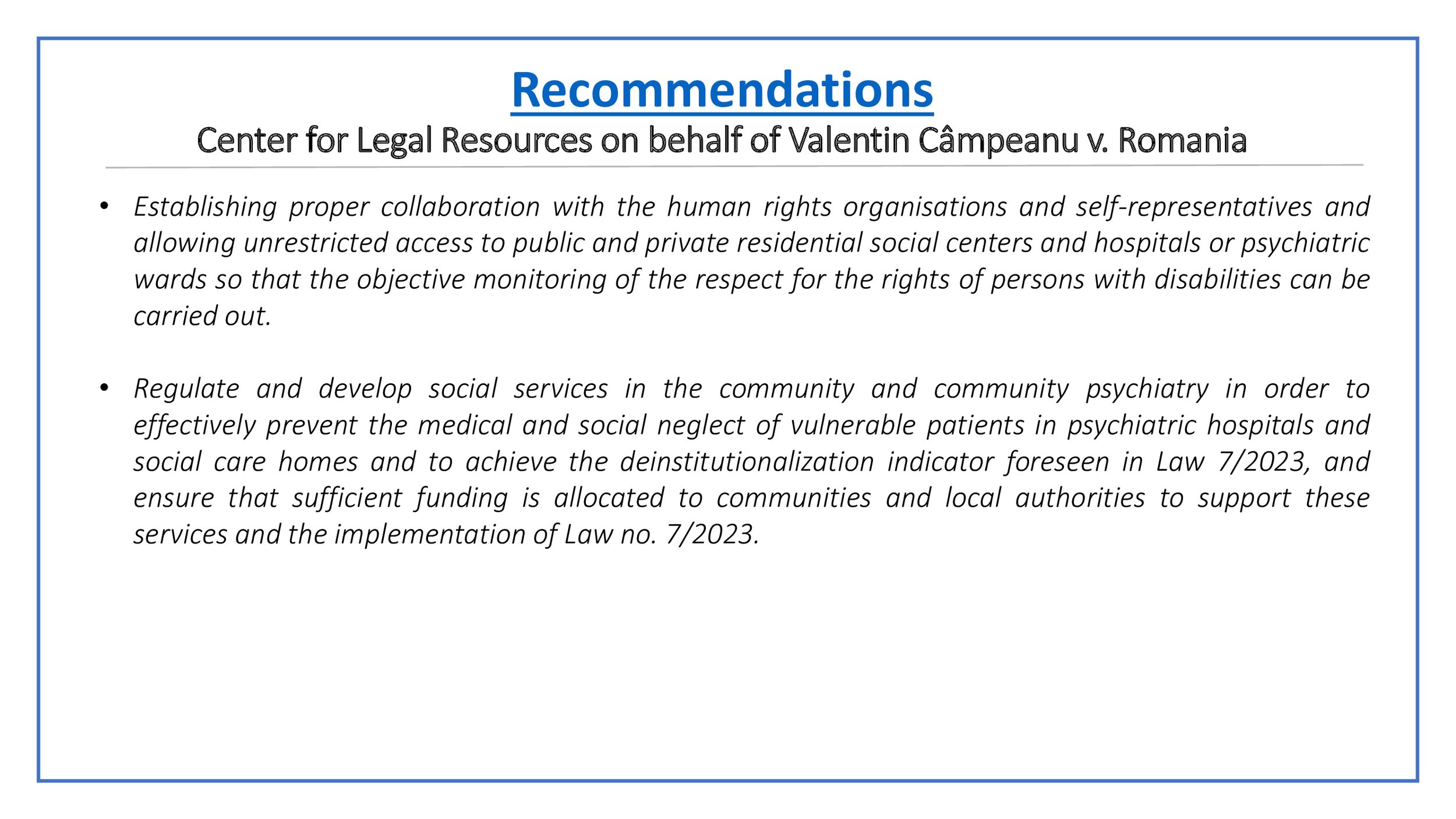

A major underlying factor causing pressure on the psychiatric and social care system in Romania, leading to these violations, is the lack of alternative community-based mental health and social care services for persons with mental disabilities, including the lack of alternative living options. When such services and alternatives are unavailable, the only resort becomes placement in psychiatric hospitals and social care homes. However, according to the Court’s rulings, the deprivation of liberty of persons with mental disabilities is unlawful when compulsory confinement is not warranted (Stanev v. Bulgaria [GC], 2012, § 145). This is also problematic under other instruments of the Council of Europe and contrary to the standards of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Compulsory psychiatric confinement (both de facto and de jure) cannot be warranted when it is caused by a lack of community services and alternatives. The overabundance of placement measures, due to lack of alternatives, leads to pressure on the mental health system, overloading it and giving way to violations.

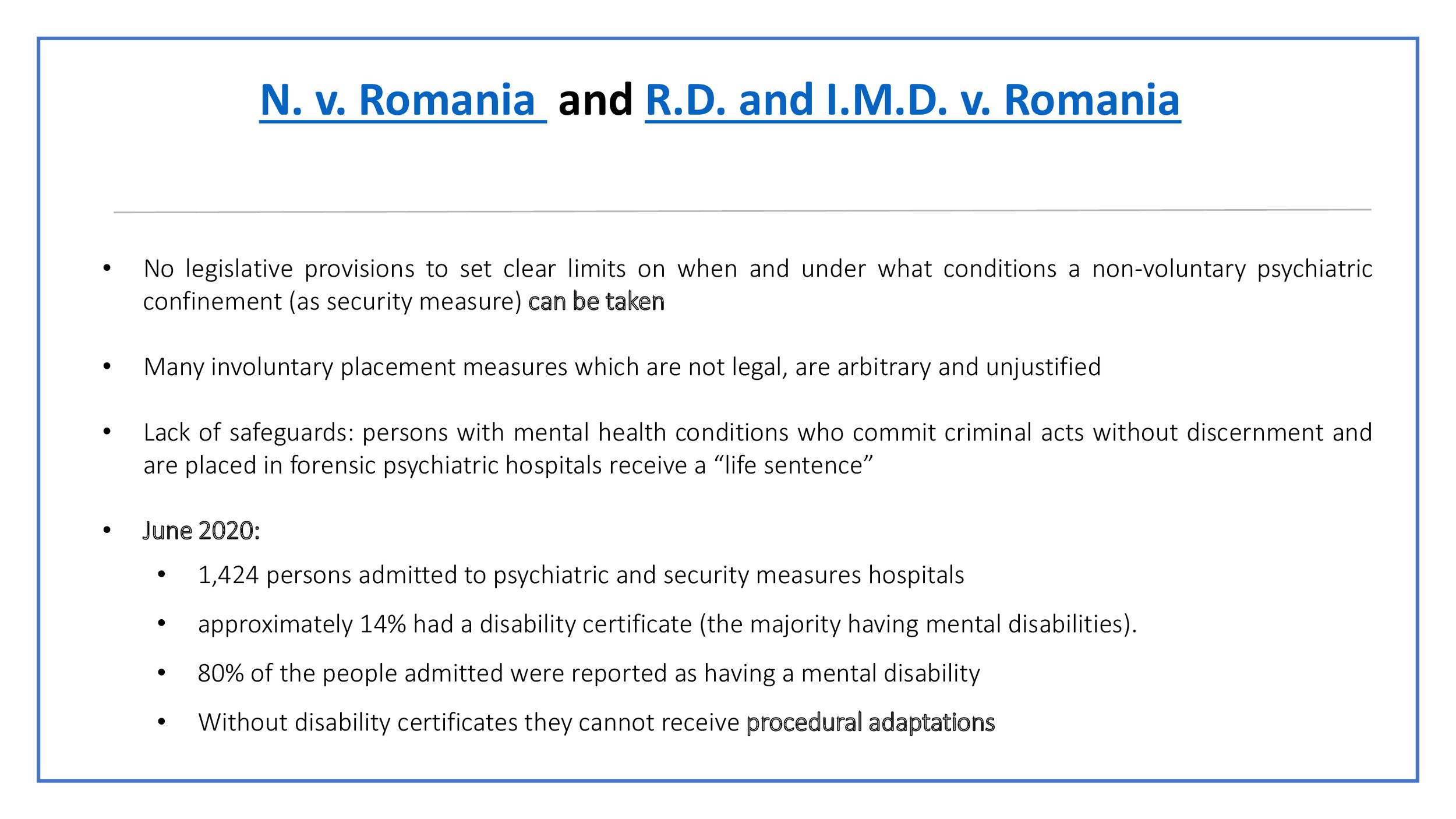

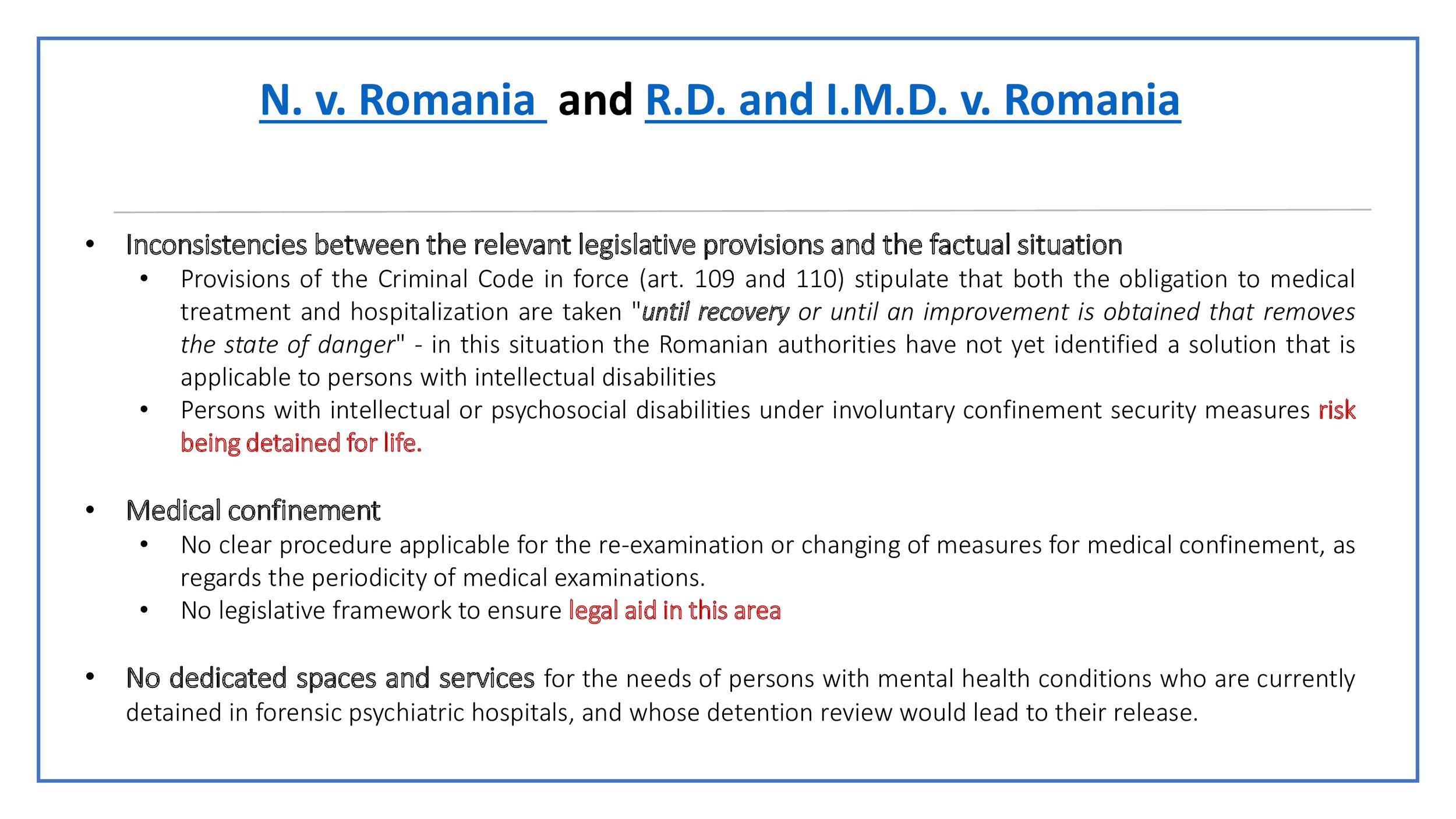

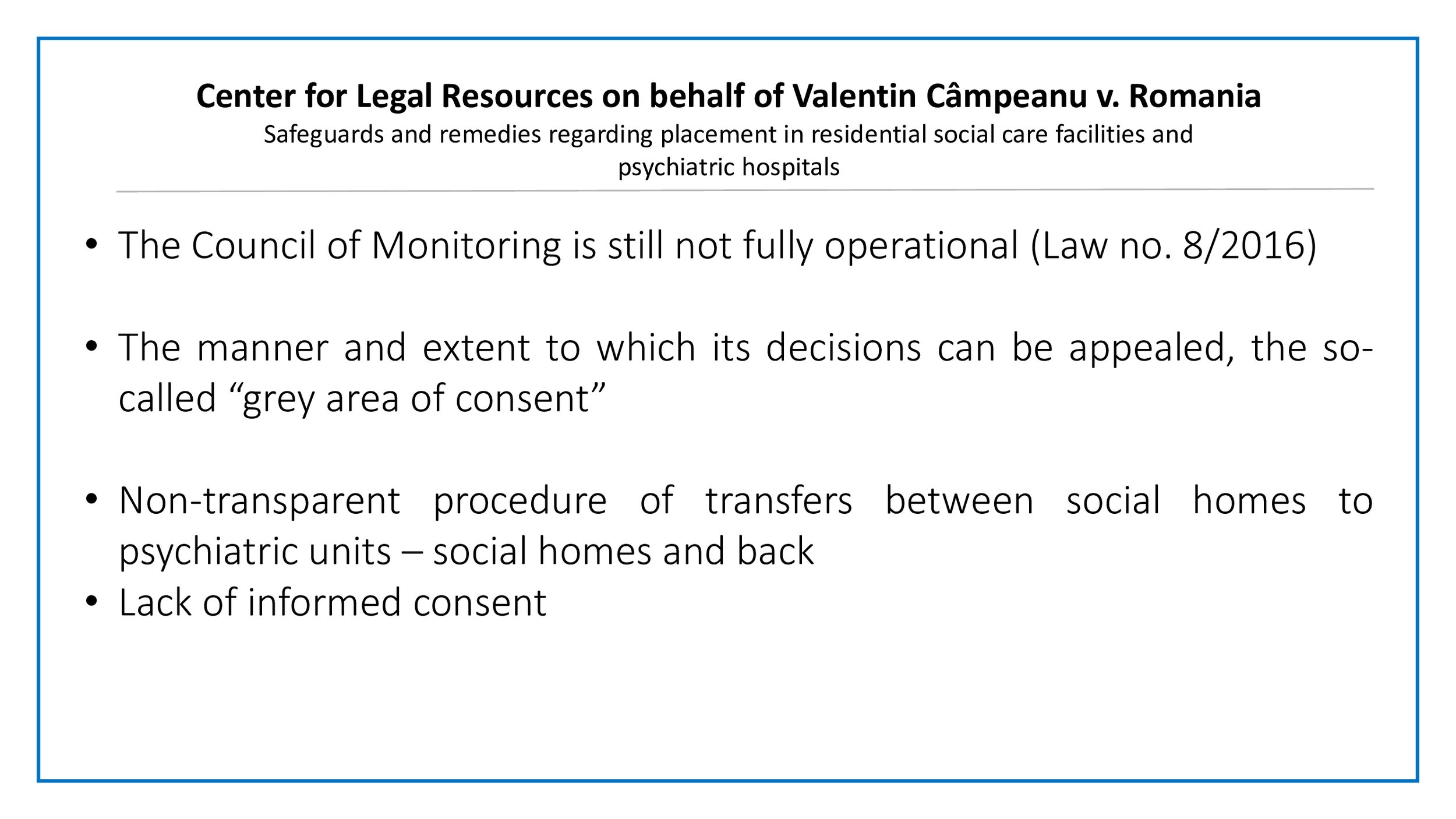

Several practices, some of which have already been identified in previous CM-DH notes in the Cristian Teodorescu v. Romania case, contribute to the perpetuation of unlawful deprivation of liberty in psychiatric hospitals and the ‘system overload’: voluntary patients are de facto involuntarily detained, without the necessary legal safeguards; patients who do not require psychiatric treatment but do not have families or suitable accommodation in social care facilities remain under involuntary placements; persons with intellectual disabilities are subjected to involuntary placements in forensic psychiatric confinement (as a security measure), despite the fact there is no case for recovery from intellectual disabilities. Such practices could be avoided if effective community-based alternatives existed.

Furthermore, the overcrowding caused by excessive unnecessary placements, and insufficient staffing, taken together, diminish the capacity of psychiatric hospitals to abide by the legal provisions and respect legal safeguards concerning placements and periodic, timely reviews.

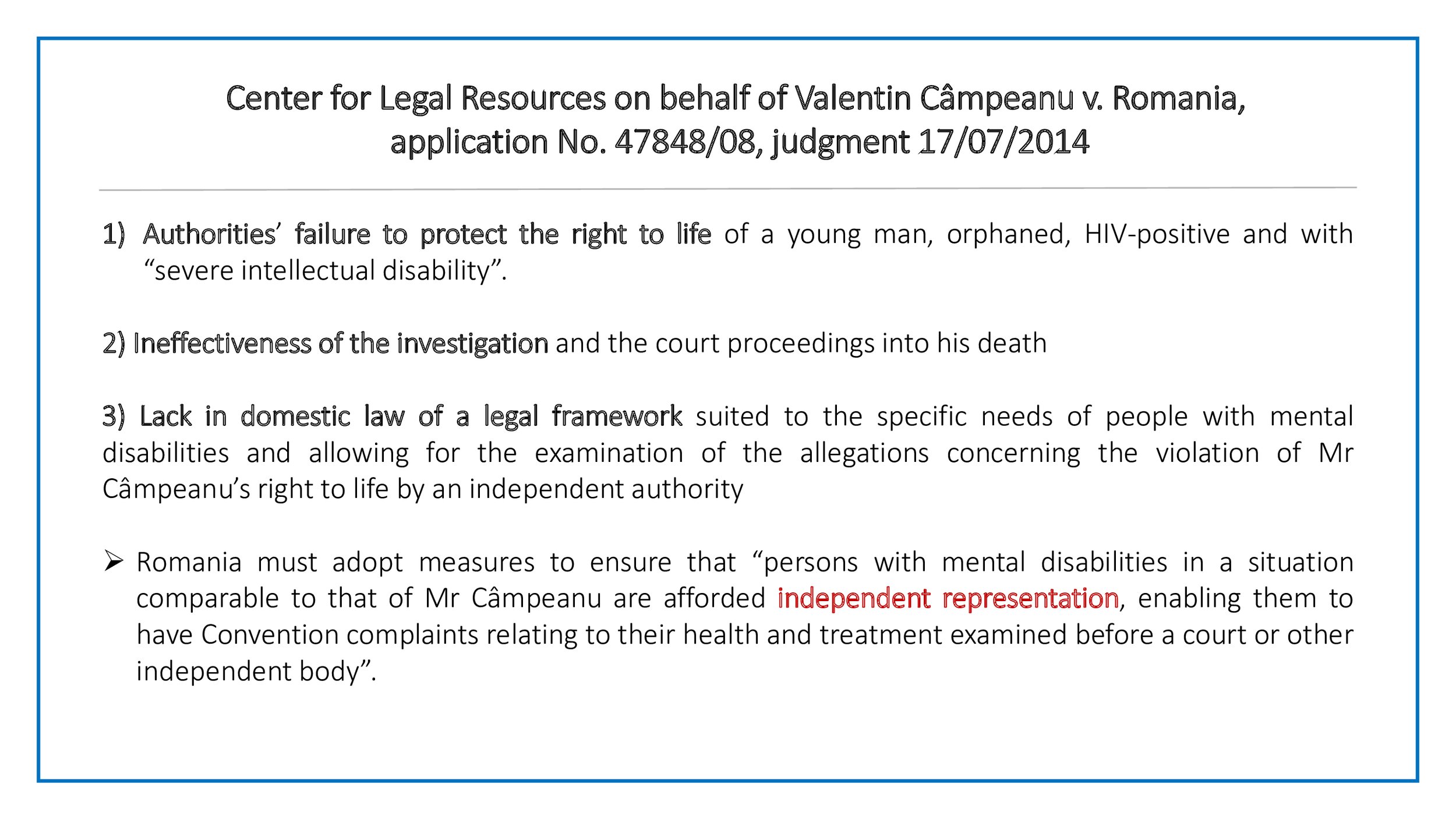

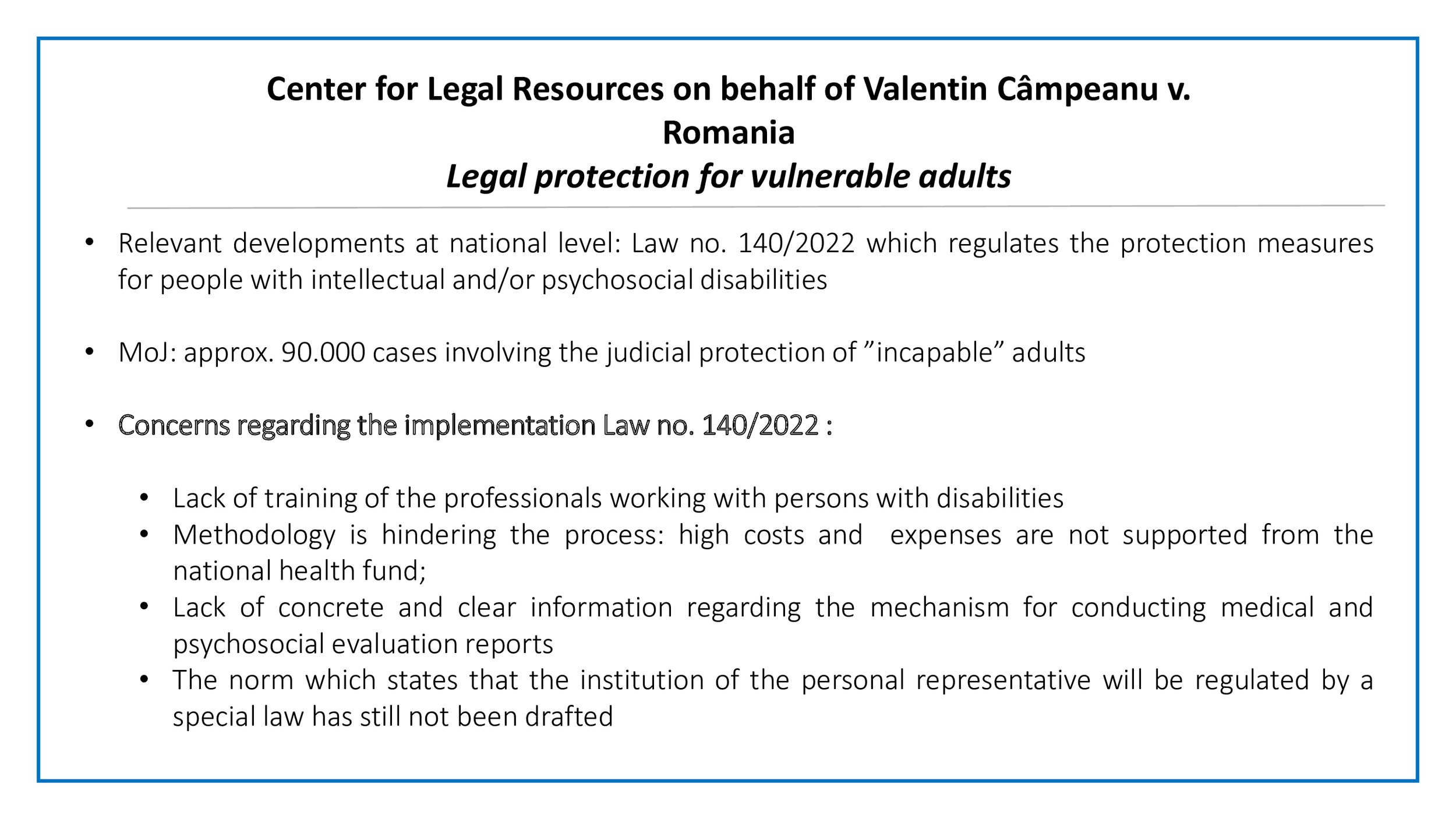

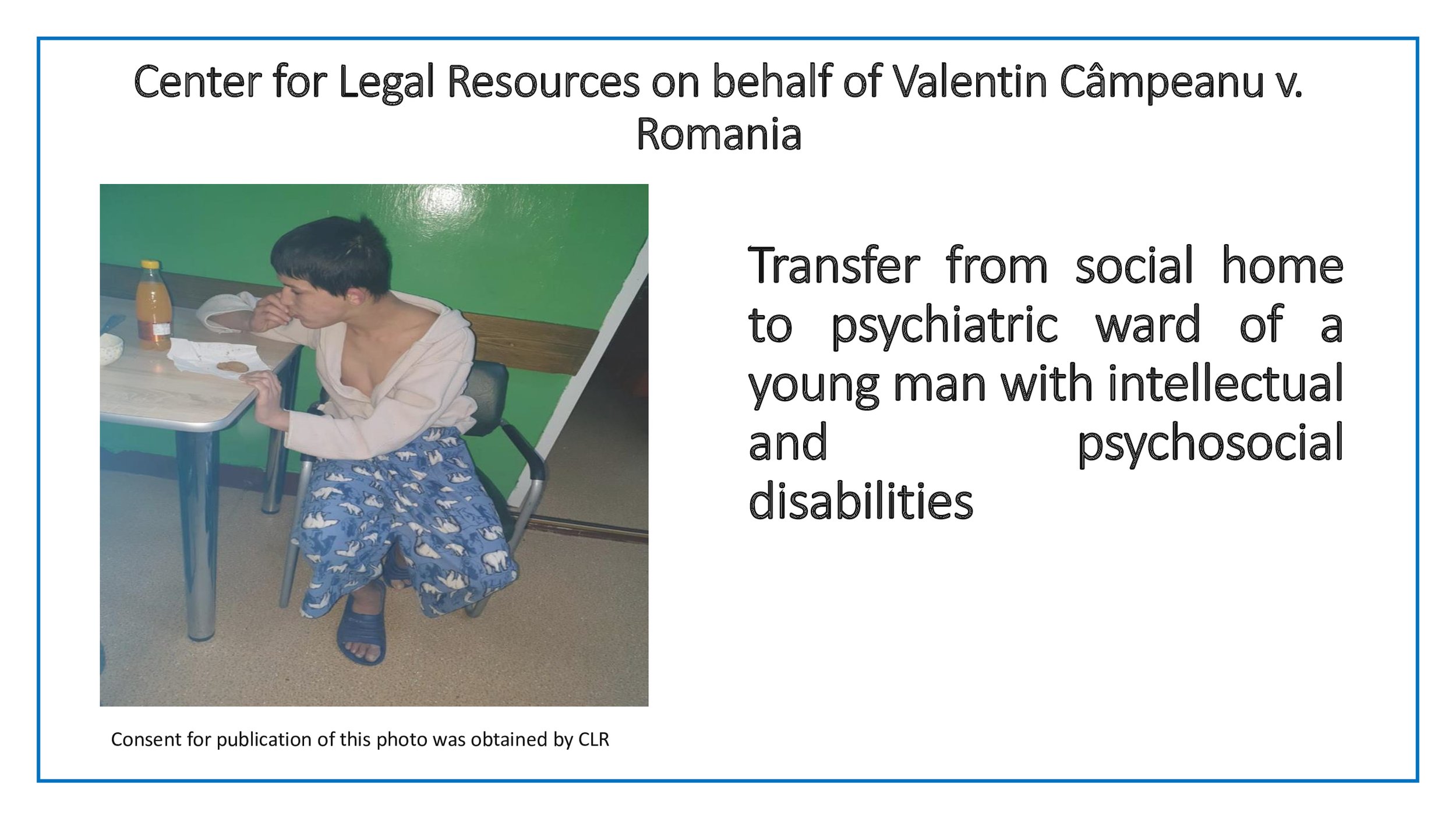

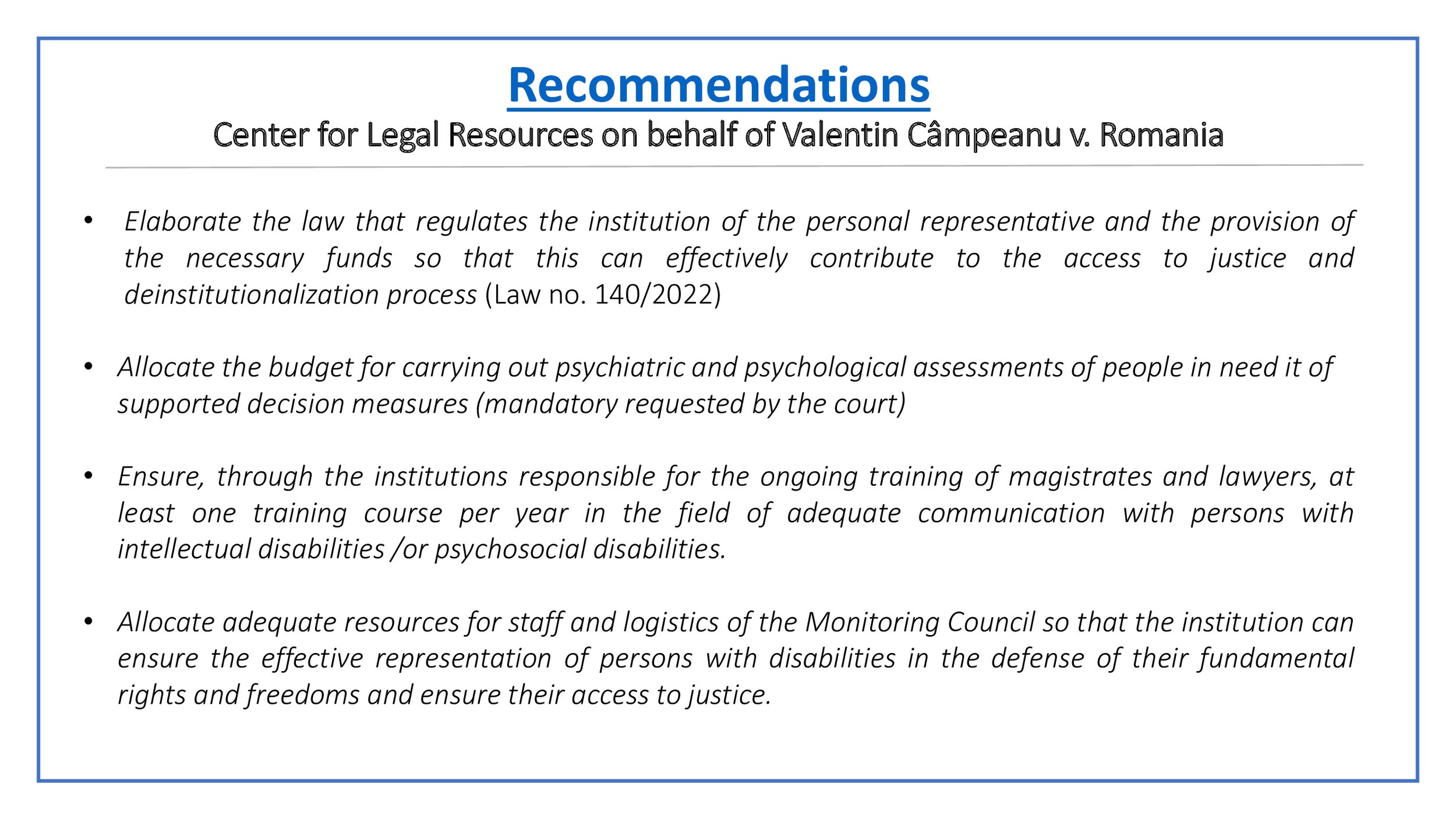

With regard to the new legal framework suited to the specific needs of people with mental disabilities[iii], which pertains to the implementation of the Centre for Legal Resources on behalf of Valentin Câmpeanu v. Romania judgment, alternative, community-based mental health and social care services are essential to ensure the effectiveness of this reform. The Romanian government, in their latest communication, discussed the new legislation on supporting the de-institutionalization process for adults with disabilities; the implementation of this law is key in ensuring the efficiency of the legal framework which is meant to provide a tailor-made responses for the independent representation of persons with disabilities. In addition, the judiciary gives weight to the living situation and independent life skills of persons with mental disabilities when assessing requests to vacate guardianship and determine protection measures.